CONTENTS

XI

ADOLFO BETTI

THE TECHNIC OF THE MODERN QUARTET

What lover of chamber music in its more

perfect dispensations is not familiar with the

figure of Adolfo Betti, the guiding brain and

bow of the Flonzaley Quartet? Born in Florence,

he played his first public concert at the

age of six, yet as a youth found it hard to

choose between literature, for which he had

decided aptitude,[A] and music. Fortunately

for American concert audiences of to-day, he

finally inclined to the latter. An exponent of

what many consider the greatest of all violinistic

schools, the Belgian, he studied for four

years with César Thomson at Liège, spent four

more concertizing in Vienna and elsewhere,

and returned to Thomson as the latter's assistant

in the Brussels Conservatory, three years

before he joined the Flonzaleys, in 1903.

With pleasant recollections of earlier meetings

with this gifted artist, the writer sought him

out, and found him amiably willing to talk

about the modern quartet and its ideals, ideals

which he personally has done so much to realize.

[A] M. Betti has published a number of critical articles in the Guide Musical of Brussels, the Rivista Musicale of Turin, etc.

THE MODERN QUARTET

"You ask me how the modern quartet differs from its predecessors?" said Mr. Betti. "It differs in many ways. For one thing the modern quartet has developed in a way that makes its inner voices—second violin and viola—much more important than they used to be. Originally, as in Haydn's early quartets, we have a violin solo with three accompanying instruments. In Beethoven's last quartets the intermediate voices have already gained a freedom and individuality which before him had not even been suspected. In these last quartets Beethoven has already set forth the principle which was to become the basis of modern polyphony: 'first of all to allow each voice to express itself freely and fully, and afterward to see what the relations were of one to the other.' In fact, no one has exercised a more revolutionary effect on the quartet than Beethoven—no one has made it attain so great a degree of progress. And surely the distance separating the quartet as Beethoven found it, from the quartet as he left it (Grand Fugue, Op. 131, Op. 132), is greater than that which lies between the Fugue Op. 132, and the most advanced modern quartet, let us say, for instance, Schönberg's Op. 7. Schönberg, by the way, has only applied and developed the principles established by Beethoven in the latter's last quartets. But in the modern quartet we have a new element, one which tends more and more to become preponderant, and which might be called orchestral rather than da camera. Smetana, Grieg, Tschaikovsky were the first to follow this path, in which the majority of the moderns, including Franck and Debussy, have followed them. And in addition, many among the most advanced modern composers strive for orchestral effects that often lie outside the natural capabilities of the strings!

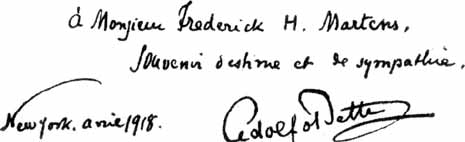

Adolfo Betti

"For instance Stravinsky, in the first of his three impressionistic sketches for quartet (which we have played), has the first violin play ponticello throughout, not the natural ponticello, but a quite special one, to produce an effect of a bag-pipe sounding at a distance. I had to try again and again till I found the right technical means to produce the effect desired. Then, the 'cello is used to imitate the drum; there are special technical problems for the second violin—a single sustained D, with an accompanying pizzicato on the open strings—while the viola is required to suggest the tramp of marching feet. And, again, in other modern quartets we find special technical devices undreamt of in earlier days. Borodine, for instance, is the first to systematically employ successions of harmonics. In the trio of his first quartet the melody is successively introduced by the 'cello and the first violin, altogether in harmonics.

THE MODERN QUARTET AND AMATEUR PLAYERS

"You ask me whether the average quartet of amateurs, of lovers of string music, can get much out of the more modern quartets. I would say yes, but with some serious reservations. There has been much beautiful music written, but most of it is complicated. In the case of the older quartets, Haydn, Mozart, etc., even if they are not played well, the performers can still obtain an idea of the music, of its thought content. But in the modern quartets, unless each individual player has mastered every technical difficulty, the musical idea does not pierce through, there is no effect.

"I remember when we rehearsed the first Schönberg quartet. It was in 1913, at a Chicago hotel, and we had no score, but only the separate parts. The results, at our first attempt, were so dreadful that we stopped after a few pages. It was not till I had secured a score, studied it and again tried it that we began to see a light. Finally there was not one measure which we did not understand. But Schönberg, Reger, Ravel quartets make too great a demand on the technical ability of the average quartet amateur.

THE TECHNIC OF QUARTET PLAYING

"Naturally, the first violin is the leader, the Conductor of the quartet, as in its early days, although the 'star' system, with one virtuose player and three satellites, has disappeared. Now the quartet as a whole has established itself in the virtuoso field—using the word virtuoso in its best sense. The Müller quartet (Hanover), 1845-1850, was the first to travel as a chamber music organization, and the famous Florentiner Quartet the first to realize what could be done in the way of finish in playing. As premier violiniste of the Flonzaley's I study and prepare the interpretation of the works we are to play before any rehearsing is done.

"While the first violin still holds first place in the modern quartet, the second violin has become much more important than formerly; it has gained in individuality. In many of the newer quartets it is quite as important as the first. In Hugo Wolf's quartet, for example, first and second violins are employed as though in a concerto for two violins.

"The viola, especially in modern French works—Ravel, Debussy, Samazeuil—has a prominent part. In the older quartets one reason the viola parts are simple is because the alto players as a rule were technically less skillful. As a general thing they were violinists who had failed—'the refugees of the G clef,' as Edouard Colonne, the eminent conductor, once wittily said. But the reason modern French composers give the viola special attention is because France now is ahead of the other nations in virtuose viola playing. It is practically the only country which may be said to have a 'school' of viola playing. In the Smetana quartet the viola plays a most important part, and Dvořák, who himself played viola, emphasized the instrument in his quartets.

"Mozart showed what the 'cello was able to do in the quartets he dedicated to the ''cellist king,' Frederick William of Prussia. And then, the 'cello has always the musical importance which attaches to it as the lower of the two 'outer voices' of the quartet ensemble. Like the second violin and viola, it has experienced a technical and musical development beyond anything Haydn or Mozart would have dared to write.

REHEARSING

"Realization of the Art aims of the modern quartet calls for endless rehearsal. Few people realize the hard work and concentrated effort entailed. And there are always new problems to solve. After preparing a new score in advance, we meet and establish its general idea, its broad outlines in actual playing. And then, gradually, we fill in the details. Ordinarily we rehearse three hours a day, less during the concert season, of course; but always enough to keep absolutely in trim. And we vary our practice programs in order to keep mentally fresh as well as technically fit.

INTONATION

"Perfect intonation is a great problem—one practically unknown to the average amateur quartet player. Four players may each one of them be playing in tune, in pitch; yet their chords may not be truly in tune, because of the individual bias—a trifle sharp, a trifle flat—in interpreting pitch. This individual bias may be caused by the attraction existing between certain notes, by differences of register and timbre, or any number of other reasons—too many to recount. The true beauty of the quartet tone cannot be obtained unless there is an exact adjustment, a tempering of the individual pitch of each instrument, till perfect accordance exists. This is far more difficult and complicated than one might at first believe. For example, let us take one of the simplest violin chords," said Mr. Betti [and he rapidly set it down in pencil].

"Now let us begin by fixing the B so that it is perfectly in tune with the E, then without at all changing the B, take the interval D-B. You will see that the sixth will not be in tune. Repeat the experiment, inverting the notes: the result will still be the same. Try it yourself some time," added Mr. Betti with a smile, "and you will see. What is the reason? It is because the middle B has not been adjusted, tempered! Give the same notes to the first and second violins and the viola and you will have the same result. Then, when the 'cello is added, the problem is still more complicated, owing to the difference in timbre and register. Yet it is a problem which can be solved, and is solved in practically everything we play.

"Another difficulty, especially in the case of some of the very daring chords encountered in modern compositions, is the matter of balance between the individual notes. There are chords which only sound well if certain notes are thrown into relief; and others only if played very softly (almost as though they were overtones). To overcome such difficulties means a great deal of work, real musical instinct and, above all, great familiarity with the composer's harmonic processes. Yet with time and patience the true balance of tone can be obtained.

TEMPO

"All four individual players must be able to feel the tempo they are playing in the same way. I believe it was Mahler who once gave out a beat very distinctly—one, two, three—told his orchestra players to count the beat silently for twenty measures and then stop. As each felt the beat differently from the other, every one of them stopped at a different time. So tempo, just like intonation, must be 'tempered' by the four quartet players in order to secure perfect rhythmic inflection.

DYNAMICS

"Modern composers have wonderfully improved dynamic expression. Every little shade of meaning they make clear with great distinctness. The older composers, and occasionally a modern like Emanuel Moor, do not use expression marks. Moor says, 'If the performers really have something to put into my work the signs are not needed.' Yet this has its disadvantages. I once had an entirely unmarked Sonata by Sammartini. As most first movements in the sonatas of that composer are allegros I tried the beginning several times as an allegro, but it sounded radically wrong. Then, at last, it occurred to me to try it as a largo and, behold, it was beautiful!

INTERPRETATION

"If the leader of the quartet has lived himself into and mastered a composition, together with his associates, the result is sure. I must live in the music I play just as an actor must live the character he represents. All higher interpretation depends on solving technical problems in a way which is not narrowly mechanical. And while the ensemble spirit must be preserved, the freedom of the individual should not be too much restrained. Once the style and manner of a modern composer are familiar, it is easier to present his works: when we first played the Reger quartet here some twenty years ago, we found pages which at first we could not at all understand. If one has fathomed Debussy, it is easier to play Milhaud, Roger-Ducasse, Samazeuil—for the music of the modern French school has much in common. One great cultural value the professional quartet has for the musical community is the fact that it gives a large circle a measure of acquaintance with the mode of thought and style of composers whose symphonic and larger works are often an unknown quantity. This applies to Debussy, Reger, the modern Russians, Bloch and others. When we played the Stravinsky pieces here, for instance, his Pétrouschka and Firebird had not yet been heard.

SOME IDEALS

"We try, as an organization, to be absolutely catholic in taste. Nor do we neglect the older music, because we play so much of the new. This year we are devoting special attention to the American composers. Formerly the Kneisels took care of them, and now we feel that we should assume this legacy. We have already played Daniel Gregory Mason's fine Intermezzo, and the other American numbers we have played include David Stanley Smith's Second Quartet, and movements from quartets by Victor Kolar and Samuel Gardner. We are also going to revive Charles Martin Loeffler's Rhapsodies for viola, oboe and piano.

"I have been for some time making a collection of sonatas a tre, two violins and 'cello—delightful old things by Sammartini, Leclair, the Englishman Boyce, Friedemann Bach and others. This is material from which the amateur could derive real enjoyment and profit. The Leclair sonata in D minor we have played some three hundred times; and its slow movement is one of the most beautiful largos I know of in all chamber music. The same thing could be done in the way of transcription for chamber music which Kreisler has already done so charmingly for the solo violin. And I would dearly love to do it! There are certain 'primitives' of the quartet—Johann Christian Bach, Gossec, Telemann, Michel Haydn—who have written music full of the rarest melodic charm and freshness. I have much excellent material laid by, but as you know," concluded Mr. Betti with a sigh, "one has so little time for anything in America."