CONTENTS

IX

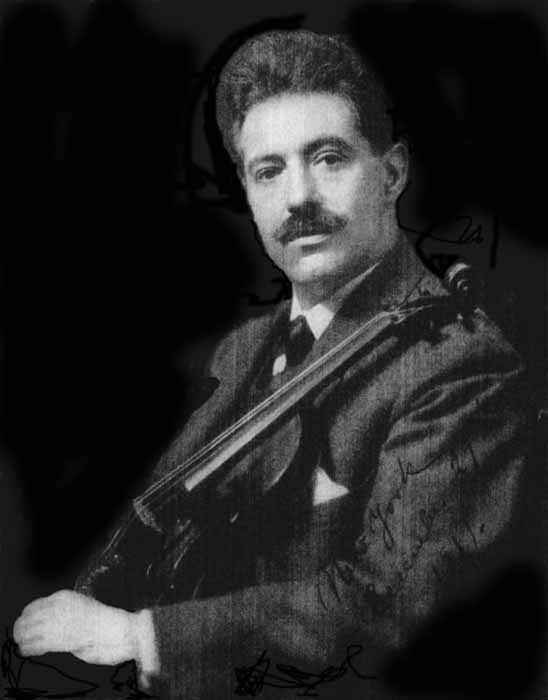

FRITZ KREISLER

PERSONALITY IN ART

The influence of the artist's personality in

his art finds a most striking exemplification in

the case of Fritz Kreisler. Some time before

the writer called on the famous violinist

to get at first hand some of his opinions

with regard to his art, he had already

met him under particularly interesting circumstances.

The question had come up of

writing text-poems for two song-adaptations

of Viennese folk-themes, airs not unattractive

in themselves; but which Kreisler's personal

touch, his individual gift of harmonization had

lifted from a lower plane to the level of the

art song. Together with the mss. of his own

beautiful transcript, Mr. Kreisler in the one

instance had given me the printed original

which suggested it—frankly a "popular" song,

clumsily harmonized in a "four-square" manner

(though written in 3/4 time) with nothing

to indicate its latent possibilities. I compared it

with his mss. and, lo, it had been transformed!

Gone was the clumsiness, the vulgar and obvious

harmonic treatment of the melody—Kreisler

had kept the melodic outline, but

etherealized, spiritualized it, given it new

rhythmic contours, a deeper and more expressive

meaning. And his rich and subtle harmonization

had lent it a quality of distinction

that justified a comparison between the grub

and the butterfly. In a small way it was an

illuminating glimpse of how the personality of

a true artist can metamorphose what at first

glance might seem something quite negligible,

and create beauty where its possibilities alone

had existed before.

It is this personal, this individual, note in all that Fritz Kreisler does—when he plays, when he composes, when he transcribes—that gives his art-effort so great and unique a quality of appeal.

Talking to him in his comfortable sitting-room in the Hotel Wellington—Homer and Juvenal (in the original) ranked on the piano-top beside De Vere Stackpole novels and other contemporary literature called to mind that though Brahms and Beethoven violin concertos are among his favorites, he does not disdain to play a Granados Spanish Dance—it seemed natural to ask him how he came to make those adaptations and transcripts which have been so notable a feature of his programs, and which have given such pleasure to thousands.

Fritz Kreisler

HOW KREISLER CAME TO COMPOSE AND ARRANGE

He said: "I began to compose and arrange as a young man. I wanted to create a repertory for myself, to be able to express through my medium, the violin, a great deal of beautiful music that had first to be adapted for the instrument. What I composed and arranged was for my own use, reflected my own musical tastes and preferences. In fact, it was not till years after that I even thought of publishing the pieces I had composed and arranged. For I was very diffident as to the outcome of such a step. I have never written anything with the commercial idea of making it 'playable.' And I have always felt that anything done in a cold-blooded way for purely mercenary considerations somehow cannot be good. It cannot represent an artist's best."

AT THE VIENNA CONSERVATORY

In reply to another query Mr. Kreisler reverted to the days when as a boy he studied at the Vienna Conservatory. "I was only seven when I attended the Conservatory and was much more interested in playing in the park, where my boy friends would be waiting for me, than in taking lessons on the violin. And yet some of the most lasting musical impressions of my life were gathered there. Not so much as regards study itself, as with respect to the good music I heard. Some very great men played at the Conservatory when I was a pupil. There were Joachim, Sarasate in his prime, Hellmesberger, and Rubinstein, whom I heard play the first time he came to Vienna. I really believe that hearing Joachim and Rubinstein play was a greater event in my life and did more for me than five years of study!"

"Of course you do not regard technic as the main essential of the concert violinist's equipment?" I asked him. "Decidedly not. Sincerity and personality are the first main essentials. Technical equipment is something which should be taken for granted. The virtuoso of the type of Ole Bull, let us say, has disappeared. The 'stunt' player of a former day with a repertory of three or four bravura pieces was not far above the average music-hall 'artist.' The modern virtuoso, the true concert artist, is not worthy of the title unless his art is the outcome of a completely unified nature.

VIOLIN MASTERY

"I do not believe that any artist is truly a master of his instrument unless his control of it is an integral part of a whole. The musician is born—his medium of expression is often a matter of accident. I believe one may be intended for an artist prenatally; but whether violinist, 'cellist or pianist is partly a matter of circumstance. Violin mastery, to my mind, still falls short of perfection, in spite of the completest technical and musical equipment, if the artist thinks only of the instrument he plays. After all, it is just a single medium of expression. The true musician is an artist with a special instrument. And every real artist has the feeling for other forms and mediums of expression if he is truly a master of his own.

TECHNIC VERSUS IMAGINATION

"I think the technical element in the artist's education is often unduly stressed. Remember," added Mr. Kreisler, with a smile, "I am not a teacher, and this is a purely personal opinion I am giving you. But it seems to me that absolute sincerity of effort, actual impossibility not to react to a genuine musical impulse are of great importance. I firmly believe that if one is destined to become an artist the technical means find themselves. The necessity of expression will follow the line of least resistance. Too great a manual equipment often leads to an exaggeration of the technical and tempts the artist to stress it unduly.

"I have worked a great deal in my life, but have always found that too large an amount of purely technico-musical work fatigued me and reacted unfavorably on my imagination. As a rule I only practice enough to keep my fingers in trim; the nervous strain is such that doing more is out of the question. And for a concert-violinist when on tour, playing every day, the technical question is not absorbing. Far more important is it for him to keep himself mentally and physically fresh and in the right mood for his work. For myself I have to enjoy whatever I play or I cannot play it. And it has often done me more good to dip my finger-tips in hot water for a few seconds before stepping out on the platform than to spend a couple of hours practicing. But I should not wish the student to draw any deductions from what I say on this head. It is purely personal and has no general application.

"Technical exercises I use very moderately. I wish my imagination to be responsive, my interest fresh, and as a rule I have found that too much work along routine channels does not accord with the best development of my Art. I feel that technic should be in the player's head, it should be a mental picture, a sort of 'master record.' It should be a matter of will power to which the manual possibilities should be subjected. Technic to me is a mental and not a manual thing.

MENTAL TECHNIC: ITS DRAWBACK AND ITS ADVANTAGE

"The technic thus achieved, a technic whose controlling power is chiefly mental, is not perfect—I say so frankly—because it is more or less dependent on the state of the artist's nervous system. Yet it is the one and only kind of technic that can adequately and completely express the musician's every instinct, wish and emotion. Every other form of technic is stiff, unpliable, since it cannot entirely subordinate itself to the individuality of the artist."

PRACTICE HOURS FOR THE ADVANCED STUDENT

Mr. Kreisler gives no lessons and hence referred this question in the most amiable manner to his boyhood friend and fellow-student Felix Winternitz, the well-known Boston violin teacher, one of the faculty of the New England Conservatory of Music, who had come in while we were talking. Mr. Winternitz did not refuse an answer: "The serious student, in my opinion, should not practice less than four hours a day, nor need he practice more than five. Other teachers may demand more. Sevčik, I know, insists that his pupils practice eight and ten hours a day. To do so one must have the constitution of an ox, and the results are often not equal to those produced by four hours of concentrated work. As Mr. Kreisler intimated with regard to technic, practice calls for brain power. Concentration in itself is not enough. There is only one way to work and if the pupil can find it he can cover the labor of weeks in an hour."

And turning to me, Mr. Winternitz added: "You must not take Mr. Kreisler too seriously when he lays no stress on his own practicing. During the concert season he has his violin in hand for an hour or so nearly every day. He does not call it practicing, and you and I would consider it playing and great playing at that. But it is a genuine illustration of what I meant when I said that one who knew how could cover the work of weeks in an hour's time."

AN EXPLANATION BY MR. WINTERNITZ

I tried to draw from the famous violinist some hint as to the secret of the abiding popularity of his own compositions and transcripts but—as those who know him are aware—Kreisler has all the modesty of the truly great. He merely smiled and said: "Frankly, I don't know." But Mr. Winternitz' comment (when a 'phone call had taken Kreisler from the room for a moment) was, "It is the touch given by his accompaniments that adds so much: a harmonic treatment so rich in design and coloring, and so varied that melodies were never more beautifully set off." Mr. Kreisler, as he came in again, remarked: "I don't mind telling you that I enjoyed very much writing my Tambourin Chinois.[A] The idea for it came to me after a visit to the Chinese theater in San Francisco—not that the music there suggested any theme, but it gave me the impulse to write a free fantasy in the Chinese manner."

[A] It is interesting to note that Nikolai Sokoloff, conductor of the San Francisco Philharmonic, returning from a tour of the American and French army camps in France, some time ago, said: "My most popular number was Kreisler's Tambourin Chinois. Invariably I had to repeat that." A strong indorsement of the internationalism of Art by the actual fighter in the trenches.

STYLE, INTERPRETATION AND THE ARTISTIC IDEAL

The question of style now came up. "I am not in favor of 'labeling' the concert artist, of calling him a 'lyric' or a 'dramatic' or some other kind of a player. If he is an artist in the real sense he controls all styles." Then, in answer to another question: "Nothing can express music but music itself. Tradition in interpretation does not mean a cut-and-dried set of rules handed down; it is, or should be, a matter of individual sentiment, of inner conviction. What makes one man an artist and keeps another an amateur is a God-given instinct for the artistically and musically right. It is not a thing to be explained, but to be felt. There is often only a narrow line of demarcation between the artistically right and wrong. Yet nearly every real artist will be found to agree as to when and when not that boundary has been overstepped. Sincerity and personality as well as disinterestedness, an expression of himself in his art that is absolutely honest, these, I believe, are ideals which every artist should cherish and try to realize. I believe, furthermore, that these ideals will come more and more into their own; that after the war there will be a great uplift, and that Art will realize to the full its value as a humanizing factor in life." And as is well known, no great artist of our day has done more toward the actual realization of these ideals he cherishes than Fritz Kreisler himself.