CONTENTS

XVII

LEON SAMETINI

HARMONICS

Leon Sametini, at present director of the

violin department of the Chicago Music College,

where Sauret, Heermann and Sebald

preceded him, is one of the most successful

teachers of his instrument in this country. It

is to be regretted that he has not played in

public in the United States as often as in

Europe, where his extensive tournées in Holland—Leon

Sametini is a Hollander by birth—Belgium,

England and Austria have established

his reputation as a virtuoso, and the

quality of his playing led Ysaye to include him

in a quartet of artists "in order of lyric expression"

with himself and Thibaud. Yet, the

fact remains that this erstwhile protégé of

Queen Wilhelmina—she gave him his beautiful

Santo Serafin (1730) violin, whose golden

varnish back "is a genuine picture,"—to quote

its owner—is a distinguished interpreting

artist besides having a real teaching gift, which

lends additional weight to his educational

views.

REMINISCENCES OF SEVČIK

"I began to study violin at the age of six, with my uncle. From him I went to Eldering in Amsterdam, now Willy Hess's successor at the head of the Cologne Conservatory, and then spent a year with Sevčik in Prague. Yet—without being his pupil—I have learned more from Ysaye than from any of my teachers. It is rather the custom to decry Sevčik as a teacher, to dwell on his absolutely mechanical character of instruction—and not without justice. First of all Sevčik laid all the stress on the left hand and not on the bow—an absolute inversion of a fundamental principle. Eldering had taken great pains with my bow technic, for he himself was a pupil of Hubay, who had studied with Vieuxtemps and had his tradition. But Sevčik's teaching as regards the use of the bow was very poor; his pupils—take Kubelik with all his marvelous finger facility—could never develop a big bow technic. Their playing lacks strength, richness of sound. Sevčik soon noticed that my bowing did not conform to his theories; yet since he could not legitimately complain of the results I secured, he did not attempt to make me change it. Musical beauty, interpretation, in Sevčik's case were all subordinated to mechanical perfection. With him the study of some inspired masterpiece was purely a mathematical process, a problem in technic and mental arithmetic, without a bit of spontaneity. Ysaye used to roar with laughter when I would tell him how, when a boy of fifteen, I played the Beethoven concerto for Sevčik—a work which I myself felt and knew it was then out of the question for me to play with artistic maturity—the latter's only criticisms on my performance were that one or two notes were a little too high, and a certain passage not quite clear.

"Sevčik did not like the Dvořák concerto and never gave it to his pupils. But I lived next door to Dvořák at Prague, and meeting him in the street one day, asked him some questions anent its interpretation, with the result that I went to his home various times and he gave me his own ideas as to how it should be played. Sevčik never pointed his teachings by playing himself. I never saw him take up the fiddle while I studied with him. While I was his pupil he paid me the compliment of selecting me to play Sinigaglia's engaging violin concerto, at short notice, for the first time in Prague. Sinigaglia had asked Sevčik to play it, who said: 'I no longer play violin, but I have a pupil who can play it for you,' and introduced me to him. Sinigaglia became a good friend of mine, and I was the first to introduce his Rapsodia Piedmontese for violin and orchestra in London. To return to Sevčik—with all the deficiencies of his teaching methods, he had one great gift. He taught his pupils how to practice! And—aside from bowing—he made all mechanical problems, especially finger problems, absolutely clear and lucid.

A QUARTET OF GREAT TEACHERS WITH WHOM

ALL MAY STUDY

"Still, all said and done, it was after I had finished with all my teachers that I really began to learn to play violin: above all from Ysaye, whom I went to hear play wherever and whenever I could. I think that the most valuable lessons I have ever had are those unconsciously given me by four of the greatest violinists I know: Ysaye, Kreisler, Elman and Thibaud. Each of these artists is so different that no one seems altogether to replace the other. Ysaye with his unique personality, the immense breadth and sweep of his interpretation, his dramatic strength, stands alone. Kreisler has a certain sparkling scintillance in his playing that is his only. Elman might be called the Caruso among violinists, with the perfected sensuous beauty of his tone; while Thibaud stands for supreme elegance and distinction. I have learned much from each member of this great quartet. And if the artist can profit from hearing and seeing them play, why not the student? Every recital given by such masters offers the earnest violin student priceless opportunities for study and comparison. My special leaning toward Ysaye is due, aside from his wonderful personality, to the fact that I feel music in the same way that he does.

TEACHING PRINCIPLES

'My teaching principles are the results of my own training period, my own experience as a concert artist and teacher—before I came to America I taught in London, where Isolde Menges, among others, studied with me—and what either directly or indirectly I have learned from my great colleagues. In the Music College I give the advanced pupils their individual lessons; but once a week the whole class assembles—as in the European conservatories—and those whose turn it is to play do so while the others listen. This is of value to every student, since it gives him an opportunity of 'hearing himself as others hear him.' Then, to stimulate appreciation and musical development there are ensemble and string quartet classes. I believe that every violinist should be able to play viola, and in quartet work I make the players shift constantly from one to the other instrument in order to hear what they play from a different angle.

"For left hand work I stick to the excellent Sevčik exercises and for some pupils I use the Carl Flesch Urstudien. For studies of real musical value Rode, of course, is unexcelled. His studies are the masterpieces of their kind, and I turn them into concert pieces. Thibaud and Elman have supplied some of them with interesting piano accompaniments.

"For bowing, with the exception of a few purely mechanical exercises, I used Kreutzer and Rode, and Gavinies. Ninety-nine per cent. of pupils' faults are faults of bowing. It is an art in itself. Sevčik was able to develop Kubelik's left hand work to the last degree of perfection—but not his bowing. In the case of Kocian, another well-known Sevčik pupil whom I have heard play, his bowing was by no means an outstanding feature. I often have to start pupils on the open strings in order to correct fundamental bow faults.

"When watching a great artist play the student should not expect to secure similar results by slavish imitation—another pupil fault. The thing to do is to realize the principle behind the artist's playing, and apply it to one's own physical possibilities.

"Every one holds, draws and uses the bow in a different way. If no two thumb-prints are alike, neither are any two sets of fingers and wrists. This is why not slavish imitation, but intelligent adaptation should be applied to the playing of the teacher in the class-room or the artist on the concert-stage. For instance, the little finger of Ysaye's left hand bends inward somewhat—as a result it is perfectly natural for him to make less use of the little finger, while it might be very difficult or almost impossible for another to employ the same fingering. And certain compositions and styles of composition are more adapted to one violinist than to another. I remember when I was a student, that Wieniawski's music seemed to lie just right for my hand. I could read difficult things of his at sight.

DOUBLE HARMONICS

"Would I care to discuss any special feature of violin technic? I might say something anent double harmonics—a subject too often taught in a mechanical way, and one I have always taken special pains to make absolutely plain to my own pupils—for every violinist should be able to play double harmonics out of a clear understanding of how to form them.

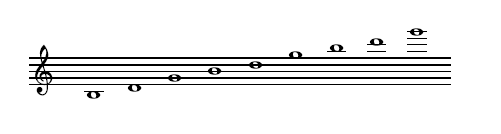

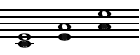

"There are only two kinds of harmonics: natural and artificial. Natural harmonics may be formed on the major triad of each open string, using the open string as the tonic. As, for example, on the G string [and Mr. Sametini set down the following illustration]:

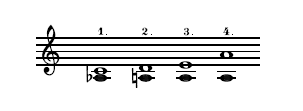

Then there are four kinds of artificial harmonics, only three of which are used: harmonics on the major third (1); harmonics on the perfect fourth (2); harmonics on the perfect fifth (3); and harmonics—never used—on the octave:

Where does the harmonic sound in each case? Two octaves and a third higher (1); two octaves higher (2); one octave and a fifth higher (3) respectively, than the pressed-down note. If the harmonic on the octave (4) were played, it would sound just an octave higher than the pressed-down note.

"Now say we wished to combine different double harmonics. The whole principle is made clear if we take, let us say, the first double-stop in the scale of C major in thirds as an example:

"Beginning with the lower of these two notes, the C, we find that it cannot not be taken as a natural harmonic

because natural harmonics on the open strings run as follows: G, B, D on the G string; D, F♯, A on the D string; A, C♯, E on the A string; and E, G♯, B on the E string. There are three ways of taking the C before mentioned as an artificial harmonic. The E may be taken in the following manner:

Nat. harmonic

Artificial harmonic

Now we have to combine the C and E as well as we are able. Rejecting the following combinations as impossible—any violinist will see why—

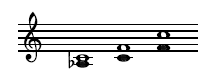

we have a choice of the two possible combinations remaining, with the fingering indicated:

"With regard to the actual execution of these harmonics, I advise all students to try and play them with every bit as much expressive feeling as ordinary notes. My experience has been that pupils do not pay nearly enough attention to the intonation of harmonics. In other words, they try to produce the harmonics immediately, instead of first making sure that both fingers are on the right spot before they loosen one finger on the string. For instance in the following:

first play

and then

then loosen the fourth finger, and play

"The same principle holds good when playing double harmonics. Nine tenths of the 'squeaking' heard when harmonics are played is due to the fact that the finger-placing is not properly prepared, and that the fingers are not on the right spot.

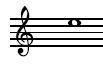

"Never, when playing a harmonic with an up-bow [Symbol: up-bow], at the point, smash down the bow on the string; but have it already on the string before playing the harmonic. The process is reversed when playing a down-bow [Symbol: down-bow] harmonic. When beginning a harmonic at the frog, have the harmonic ready, then let the bow drop gently on the string.

"Triple and quadruple harmonics may be combined in exactly the same way. Students should never get the idea that you press down the string as you press a button and—presto—the magic harmonics appear! They are a simple and natural result of the proper application of scientific principles; and the sooner the student learns to form and combine harmonics himself instead of learning them by rote, the better will he play them. Too often a student can give the fingering of certain double harmonics and cannot use it. Of course, harmonics are only a detail of the complete mastery of the violin; but mastery of all details leads to mastery of the whole.

VIOLIN MASTERY

"And what is mastery of the whole? Mastery of the whole, real violin mastery, I think, lies in the control of the interpretative problem, the power to awaken emotion by the use of the instrument. Many feel more than they can express, have more left hand than bow technic and, like Kubelik, have not the perfected technic for which perfected playing calls. The artist who feels beauty keenly and deeply and whose mechanical equipment allows him to make others feel and share the beauty he himself feels is in my opinion worthy of being called a master of the violin."