CONTENTS

VII

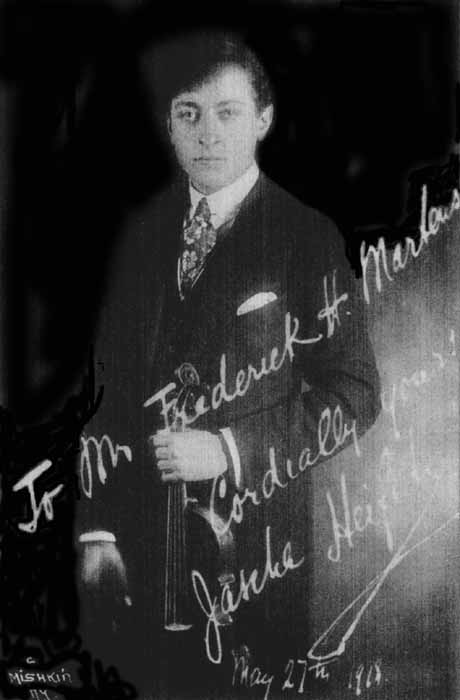

JASCHA HEIFETZ

THE DANGER OF PRACTICING TOO MUCH.

TECHNICAL MASTERY

AND TEMPERAMENT

Mature in virtuosity—the modern virtuosity

which goes so far beyond the mere technical

mastery that once made the term a reproach—though

young in years, Jascha Heifetz, when

one makes his acquaintance "off-stage," seems

singularly modest about the great gifts which

have brought him international fame. He is

amiable, unassuming and—the best proof, perhaps,

that his talent is a thing genuine and inborn,

not the result of a forcing process—he

has that broad interest in art and in life going

far beyond his own particular medium, the

violin, without which no artist may become

truly great. For Jascha Heifetz, with his

wonderful record of accomplishment achieved,

and with triumphs still to come before him,

does not believe in "all work and no play."

Jascha Heifetz

THE DANGER OF PRACTICING TOO MUCH

He laughed when I put forward the theory that he worked many hours a day, perhaps as many as six or eight? "No," he said, "I do not think I could ever have made any progress if I had practiced six hours a day. In the first place I have never believed in practicing too much—it is just as bad as practicing too little! And then there are so many other things I like to do. I am fond of reading and I like sport: tennis, golf, bicycle riding, boating, swimming, etc. Often when I am supposed to be practicing hard I am out with my camera, taking pictures; for I have become what is known as a 'camera fiend.' And just now I have a new car, which I have learned to drive, and which takes up a good deal of my time. I have never believed in grinding. In fact I think that if one has to work very hard to get his piece, it will show in the execution. To interpret music properly, it is necessary to eliminate mechanical difficulty; the audience should not feel the struggle of the artist with what are considered hard passages. I hardly ever practice more than three hours a day on an average, and besides, I keep my Sunday when I do not play at all, and sometimes I make an extra holiday. As to six or seven hours a day, I would not have been able to stand it at all."

I implied that what Mr. Heifetz said might shock thousands of aspiring young violinists for whom he pointed a moral: "Of course," his answer was, "you must not take me too literally. Please do not think because I do not favor overdoing practicing that one can do without it. I'm quite frank to say I could not myself. But there is a happy medium. I suppose that when I play in public it looks easy, but before I ever came on the concert stage I worked very hard. And I do yet—but always putting the two things together, mental work and physical work. And when a certain point of effort is reached in practice, as in everything else, there must be relaxation.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF A VIRTUOSE TECHNIC

"Have I what is called a 'natural' technic? It is hard for me to say, perhaps so. But if such is the case I had to develop it, to assure it, to perfect it. If you start playing at three, as I did, with a little violin one-quarter of the regular size, I suppose violin playing becomes second nature in the course of time. I was able to find my way about in all seven positions within a year's time, and could play the Kayser études; but that does not mean to say I was a virtuoso by any means.

"My first teacher? My first teacher was my father, a good violinist and concertmaster of the Vilna Symphony Orchestra. My first appearance in public took place in an overcrowded auditorium of the Imperial Music School in Vilna, Russia, when I was not quite five. I played the Fantaisie Pastorale with piano accompaniment. Later, at the age of six, I played the Mendelssohn concerto in Kovno to a full house. Stage-fright? No, I cannot say I have ever had it. Of course, something may happen to upset one before a concert, and one does not feel quite at ease when first stepping on the stage; but then I hope that is not stage-fright!

"At the Imperial Music School in Vilna, and before, I worked at all the things every violinist studies—I think that I played almost everything. I did not work too hard, but I worked hard enough. In Vilna my teacher was Malkin, a pupil of Professor Auer, and when I had graduated from the Vilna school I went to Auer. Did I go directly to his classes? Well, no, but I had only a very short time to wait before I joined the classes conducted by Auer personally.

PROFESSOR AUER AS A TEACHER

"Yes, he is a wonderful and an incomparable teacher; I do not believe there is one in the world who can possibly approach him. Do not ask me just how he does it, for I would not know how to tell you. But he is different with each pupil—perhaps that is one reason he is so great a teacher. I think I was with Professor Auer about six years, and I had both class lessons and private lessons of him, though toward the end my lessons were not so regular. I never played exercises or technical works of any kind for the Professor, but outside of the big things—the concertos and sonatas, and the shorter pieces which he would let me prepare—I often chose what I wanted.

"Professor Auer was a very active and energetic teacher. He was never satisfied with a mere explanation, unless certain it was understood. He could always show you himself with his bow and violin. The Professor's pupils were supposed to have been sufficiently advanced in the technic necessary for them to profit by his wonderful lessons in interpretation. Yet there were all sorts of technical finesses which he had up his sleeve, any number of fine, subtle points in playing as well as interpretation which he would disclose to his pupils. And the more interest and ability the pupil showed, the more the Professor gave him of himself! He is a very great teacher! Bowing, the true art of bowing, is one of the greatest things in Professor Auer's teaching. I know when I first came to the Professor, he showed me things in bowing I had never learned in Vilna. It is hard to describe in words (Mr. Heifetz illustrated with some of those natural, unstrained movements of arm and wrist which his concert appearances have made so familiar), but bowing as Professor Auer teaches it is a very special thing; the movements of the bow become more easy, graceful, less stiff.

"In class there were usually from twenty-five to thirty pupils. Aside from what we each gained individually from the Professor's criticism and correction, it was interesting to hear the others who played before one's turn came, because one could get all kinds of hints from what Professor Auer told them. I know I always enjoyed listening to Poliakin, a very talented violinist, and Cécile Hansen, who attended the classes at the same time I did. The Professor was a stern and very exacting, but a sympathetic, teacher. If our playing was not just what it should be he always had a fund of kindly humor upon which to draw. He would anticipate our stock excuses and say: 'Well, I suppose you have just had your bow rehaired!' or 'These new strings are very trying,' or 'It's the weather that is against you again, is it not?' or something of the kind. Examinations were not so easy: we had to show that we were not only soloists, but also sight readers of difficult music.

A DIFFICULTY OVERCOME

"The greatest technical difficulty I had when I was studying?" Jascha Heifetz tried to recollect, which was natural, seeing that it must have been one long since overcome. Then he remembered, and smiled: "Staccato playing. To get a good staccato, when I first tried seemed very hard to me. When I was younger, really, at one time I had a very poor staccato!" [I assured the young artist that any one who heard him play here would find it hard to believe this.] "Yes, I did," he insisted, "but one morning, I do not know just how it was—I was playing the cadenza in the first movement of Wieniawski's F♯ minor concerto,—it is full of staccatos and double stops—the right way of playing staccato came to me quite suddenly, especially after Professor Auer had shown me his method.

VIOLIN MASTERY

"Violin Mastery? To me it means the ability to make the violin a perfectly controlled instrument guided by the skill and intelligence of the artist, to compel it to respond in movement to his every wish. The artist must always be superior to his instrument, it must be his servant, one that he can do with what he will.

TECHNICAL MASTERY AND TEMPERAMENT

"It appears to me that mastery of the technic of the violin is not so much of a mechanical accomplishment as it is of mental nature. It may be that scientists can tell us how through persistency the brain succeeds in making the fingers and the arms produce results through the infinite variety of inexplicable vibrations. The sweetness of tone, its melodiousness, its legatos, octaves, trills and harmonics all bear the mark of the individual who uses his strings like his vocal chords. When an artist is working over his harmonics, he must not be impatient and force purity, pitch, or the right intonation. He must coax the tone, try it again and again, seek for improvements in his fingering as well as in his bowing at the same time, and sometimes he may be surprised how, quite suddenly, at the time when he least expects it, the result has come. More than one road leads to Rome! The fact is that when you get it, you have it, that's all! I am perfectly willing to disclose to the musical profession all the secrets of the mastery of violin technic; but are there any secrets in the sense that some of the uninitiated take them? If an artist happens to excel in some particular, he is at once suspected of knowing some secret means of so doing. However, that may not be the case. He does it just because it is in him, and as a rule he accomplishes this through his mental faculties more than through his mechanical abilities. I do not intend to minimize the value of great teachers who prove to be important factors in the life of a musician; but think of the vast army of pupils that a master teacher brings forth, and listen to the infinite variety of their spiccatos, octaves, legatos, and trills! For the successful mastery of violin technic let each artist study carefully his own individuality, let him concentrate his mental energy on the quality of pitch he intends to produce, and sooner or later he will find his way of expressing himself. Music is not only in the fingers or in the elbow. It is in that mysterious EGO of the man, it is his soul; and his body is like his violin, nothing but a tool. Of course, the great master must have the tools that suit him best, and it is the happy combination that makes for success.

"By the vibrations and modulations of the notes one may recognize the violinist as easily as we recognize the singer by his voice. Who can explain how the artist harmonizes the trilling of his fingers with the emotions of his soul?

"An artist will never become great through mere imitation, and never will he be able to attain the best results only by methods adopted by others. He must have his own initiative, although he will surely profit by the experience of others. Of course there are standard ways of approaching the study of violin technic; but these are too well known to dwell upon them: as to the niceties of the art, they must come from within. You can make a musician but not an artist!

REPERTORY AND PROGRAMS

"Which of the master works do I like best? Well, that is rather hard to answer. Each master work has its own beauties. Naturally one likes best what one understands best, I prefer to play the classics like Brahms, Beethoven, Mozart, Bach, Mendelssohn, etc. However, I played Bruch's G minor in 1913 at the Leipzig Gewandhouse with Nikisch, where I was told that Joachim was the only other violinist as young as myself to appear there as soloist with orchestra; there is the Tschaikovsky concerto which I played in Berlin in 1912, with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra with Nikisch. Alsa Bruch's D minor and many more. I played the Mendelssohn concerto in 1914, in Vienna, with Safonoff as conductor. Last season in Chicago I played the Brahms concerto with a fine and very elaborate cadenza by Professor Auer. I think the Brahms concerto for violin is like Chopin's music for piano, in a way, because it stands technically and musically for something quite different and distinct from other violin music, just as Chopin does from other piano music. The Brahms concerto is not technically as hard as, say, Paganini—but in interpretation!... And in the Beethoven concerto, too, there is a simplicity, a kind of clear beauty which makes it far harder to play than many other things technically more advanced. The slightest flaw, the least difference in pitch, in intonation, and its beauty suffers.

"Yes, there are other Russian concertos besides the Tschaikovsky. There is the Glazounov concerto and others. I understand that Zimbalist was the first to introduce it in this country, and I expect to play it here next season.

"Of course one cannot always play concertos, and one cannot always play Bach and Beethoven. And that makes it hard to select programs. The artist can always enjoy the great music of his instrument; but an audience wants variety. At the same time an artist cannot play only just what the majority of the audience wants. I have been asked to play Schubert's Ave Maria, or Beethoven's Chorus of Dervishes at every one of my concerts, but I simply cannot play them all the time. I am afraid if program making were left altogether to audiences the programs would become far too popular in character; though audiences are just as different as individuals. I try hard to balance my programs, so that every one can find something to understand and enjoy. I expect to prepare some American compositions for next season. Oh, no, not as a matter of courtesy, but because they are really fine, especially some smaller pieces by Spalding, Cecil Burleigh and Grasse!"

On concluding our interview Mr. Heifetz made a remark which is worth repeating, and which many a music lover who is plus royaliste que le roi might do well to remember: "After all," he said, "much as I love music, I cannot help feeling that music is not the only thing in life. I really cannot imagine anything more terrible than always to hear, think and make music! There is so much else to know and appreciate; and I feel that the more I learn and know of other things the better artist I will be!"