CONTENTS

V

SAMUEL GARDNER

TECHNIC AND MUSICIANSHIP

Samuel Gardner, though born in Jelisavetgrad,

Cherson province, in Southern Russia,

in 1891, is to all intents and purposes an

American, since his family, fleeing the tyranny

of an Imperialistic regime of "pogroms"

and "Black Hundreds," brought him

to this country when a mere child; and here in

the United States he has become, to quote

Richard Aldrich, "the serious and accomplished

artist," whose work on the concert

stage has given such pleasure to lovers of violin

music at its best. The young violinist, who in

the course of the same week had just won two

prizes in composition—the Pulitzer Prize

(Columbia) for a string quartet, and the Loeb

Prize for a symphonic poem—was amiably

willing to talk of his study experience for the

benefit of other students.

CHARLES MARTIN LOEFFLER AND

FELIX WINTERNITZ AS TEACHERS

"I took up the study of the violin at the age of seven, and when I was nine I went to Charles Martin Loeffler and really began to work seriously. Loeffler was a very strict teacher and very exacting, but he achieved results, for he had a most original way of making his points clear to the student. He started off with the Sevčik studies, laying great stress on the proper finger articulation. And he taught me absolute smoothness in change of position when crossing the strings. For instance, in the second book of Sevčik's 'Technical Exercises,' in the third exercise, the bow crosses from G to A, and from D to E, leaving a string between in each crossing. Well, I simply could not manage to get to the second string to be played without the string in between sounding! Loeffler showed me what every good fiddler must learn to do: to leap from the end of the down-bow to the up-bow and vice versa and then hesitate the fraction of a moment, thus securing a smooth, clean-cut tone, without any vibration of the intermediate string. Loeffler never gave a pupil any rest until he came up to his requirements. I know when I played the seventh and eighth Kreutzer studies for him—they are trill studies—he said: 'You trill like an electric bell, but not fast enough!' And he kept at me to speed up my tempo without loss of clearness or tone-volume, until I could do justice to a rapid trill. It is a great quality in a teacher to be literally able to enforce the pupil's progress in certain directions; for though the latter may not appreciate it at the time, later on he is sure to do so. I remember once when he was trying to explain the perfect crescendo to me, fire-engine bells began to ring in the distance, the sound gradually drawing nearer the house in Charles Street where I was taking my lesson. 'There you have it!' Loeffler cried: 'There's your ideal crescendo! Play it like that and I will be satisfied!' I remained with Loeffler a year and a half, and when he went to Paris began to study with Felix Winternitz.

"Felix Winternitz was a teacher who allowed his pupils to develop individuality. 'I care nothing for theories,' he used to say, 'so long as I can see something original in your work!' He attached little importance to the theory of technic, but a great deal to technical development along individual lines. And he always encouraged me to express myself freely, within my limitations, stressing the musical side of my work. With him I played through the concertos which, after a time, I used for technical material, since every phase of technic and bowing is covered in these great works. I was only fifteen when I left Winternitz and still played by instinct rather than intellectually. I still used my bow arm somewhat stiffly, and did not think much about phrasing. I instinctively phrased whatever the music itself made clear to me, and what I did not understand I merely played.

KNEISEL'S TEACHING METHODS

"But when I came to Franz Kneisel, my last teacher, I began to work with my mind. Kneisel showed me that I had to think when I played. At first I did not realize why he kept at me so insistently about phrasing, interpretation, the exact observance of expression marks; but eventually it dawned on me that he was teaching me to read a soul into each composition I studied.

"I practiced hard, from four to five hours a day. Fortunately, as regards technical equipment, I was ready for Kneisel's instruction. The first thing he gave me to study was, not a brilliant virtuoso piece, but the Bach concerto in E major, and then the Viotti concerto. In the beginning, until Kneisel showed me, I did not know what to do with them. This was music whose notes in themselves were easy, and whose difficulties were all of an individual order. But intellectual analysis, interpretation, are Kneisel's great points. A strict teacher, I worked with him for five years, the most remarkable years of all my violin study.

"Kneisel knows how to develop technical perfection without using technical exercises. I had already played the Mendelssohn, Bruch and Lalo concertos with Winternitz, and these I now restudied with Kneisel. In interpretation he makes clear every phrase in its relation to every other phrase and the movement as a whole. And he insists on his pupils studying theory and composition—something I had formerly not been inclined to take seriously.

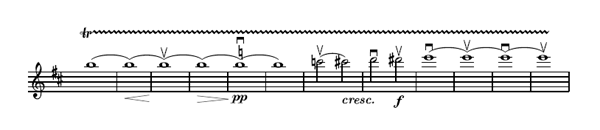

"Some teachers are satisfied if the student plays his notes correctly, in a general way. With Kneisel the very least detail, a trill, a scale, has to be given its proper tone-color and dynamic shading in absolute proportion with the balancing harmonies. This trill, in the first movement of the Beethoven concerto—(and Mr. Gardner jotted it down)

Kneisel kept me at during the entire lesson, till I was able to adjust its tone-color and nuances to the accompanying harmony. Then, though many teachers do not know it, it is a tradition in the orchestra to make a diminuendo in the sixth measure, before the change of key to C major, and this diminuendo should, of course, be observed by the solo instrument as well. Yet you will hear well-known artists play the trill throughout with a loud, brilliant tone and no dynamic change!

"Kneisel makes it a point to have all his pupils play chamber music because of its truly broadening influence. And he is unexcelled in taking apart structurally the Beethoven, Brahms, Tschaikovsky and other quartets, in analyzing and explaining the wonderful planning and building up of each movement. I had the honor of playing second violin in the Kneisel Quartet from September to February (1914-1915), at the outbreak of the war, a most interesting experience. The musicianship Kneisel had given me; I was used to his style and at home with his ideas, and am happy to think that he was satisfied. A year later as assistant concertmaster in the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, I had a chance to become practically acquainted with the orchestral works of Strauss, d'Indy and other moderns, and enjoy the Beethoven, Brahms and Tschaikovsky symphonies as a performer.

TECHNIC AND MUSICIANSHIP

"How do I regard technic now? I think of it in the terms of the music itself. Music should dictate the technical means to be used. The composition and its phrases should determine bowing and the tone quality employed. One should not think of down-bows or up-bows. In the Brahms concerto you can find many long phrases: they cannot be played with one bow; yet there must be no apparent change of bow. If the player does not know what the phrase means; how to interpret it, how will he be able to bow it correctly?

"And there are so many different nuances, especially in legato. It is as a rule produced by a slurred bow; yet it may also be produced by other bowings. To secure a good legato tone watch the singer. The singer can establish the perfect smoothness that legato calls for to perfection. To secure a like effect the violinist should convey the impression that there is no point, no frog, that the bow he uses is of indefinite length. And the violinist should never think: 'I must play this up-bow or down-bow.' Artists of the German school are more apt to begin a phrase with a down-bow; the French start playing a good deal at the point. Up or down, both are secondary to finding out, first of all, what quality, what balance of tone the phrase demands. The conductor of a symphonic orchestra does not care how, technically, certain effects are produced by the violins, whether they use an up-bow or a down-bow. He merely says: 'That's too heavy: give me less tone!' The result to be achieved is always more important than the manner of achievement.

"All phases of technical accomplishment, if rightly acquired, tend to become second nature to the player in the course of time: staccato, a brilliant trick; spiccato, the reiteration of notes played from the wrist, etc. The martellato, a nuance of spiccato, should be played with a firm bowing at the point. In a very broad spiccato, the arm may be brought into play; but otherwise not, since it makes rapid playing impossible. Too many amateurs try to play spiccato from the arm. And too many teachers are contented with a trill that is merely brilliant. Kneisel insists on what he calls a 'musical trill,' of which Kreisler's beautiful trill is a perfect example. The trill of some violinists is invariably brilliant, whether brilliancy is appropriate or not. Brilliant trills in Bach always seem out of place to me; while in Paganini and in Wieniawski's Carnaval de Venise a high brilliant trill is very effective.

"As to double-stops—Edison once said that violin music should be written only in double-stops—I practice them playing first the single notes and then the two together, and can recommend this mode of practice from personal experience. Harmonics, where clarity is the most important thing, are mainly a matter of bowing, of a sure attack and sustaining by the bow. Of course the harmonics themselves are made by the fingers; but their tone quality rests altogether with the bow.

EDISON AND OCTAVES

"The best thing I've ever heard said of octaves was Edison's remark to me that 'They are merely a nuisance and should not be played!' I was making some records for him during the experimental stage of the disk record, when he was trying to get an absolutely smooth legato tone, one that conformed to Loeffler's definition of it as 'no breaks' in the tone. He had had Schubert's Ave Maria recorded by Flesch, MacMillan and others, and wanted me to play it for him. The records were all played for me, and whenever he came to the octave passages Edison would say: 'Listen to them! How badly they sound!' Yet the octaves were absolutely in tune! 'Why do they sound so badly?' I inquired.

"Then Edison explained to me that according to the scientific theory of vibration, the vibrations of the higher tone of the octaves should be exactly twice those of the lower note. 'But here,' he continued, 'the vibrations of the notes all vary.' 'Yet how can the player control his fingers in the vibrato beyond playing his octaves in perfect tune?' I asked. 'Well, if he cannot do so,' said Edison, 'octaves are merely a nuisance, and should not be played at all.' I experimented and found that by simply pressing down the fingers and playing without any vibrato, I could come pretty near securing the exact relation between the vibrations of the upper and lower notes but—they sounded dreadful! Of course, octaves sound well in ensemble, especially in the orchestra, because each player plays but a single note. And tenths sound even better than octaves when two people play them.

WIRE AND GUT STRINGS

"You ask about my violin? It belonged to the famous Hawley collection, and is a Giovanni Baptista Guadignini, made in 1780, in Turin. The back is a single piece of maple-wood, having a broadish figure extending across its breadth. The maple-wood sides match the back. The top is formed of a very choice piece of spruce, and it is varnished a deep golden-red. It has a remarkably fine tone, very vibrant and with great carrying power, a tone that has all that I can ask for as regards volume and quality.

"I think that wire strings are largely used now-a-days because gut strings are hard to obtain—not because they are better. I do not use wire strings. I have tried them and find them thin in tone, or so brilliant that their tone is too piercing. Then, too, I find that the use of a wire E reduces the volume of tone of the other strings. No wire string has the quality of a fine gut string; and I regard them only as a substitute in the case of some people, and a convenience for lazy ones.

VIOLIN MASTERY

"Violin Mastery? Off-hand I might say the phrase stands for a life-time of effort with its highest aims unattained. As I see it the achievement of violin mastery represents a combination of 90 per cent. of toil and 10 per cent. of talent or inspiration. Goetschius, with whom I studied composition, once said to me: 'I do not congratulate you on having talent. That is a gift. But I do congratulate you on being able to work hard!' The same thing applies to the fiddle. It seems to me that only by keeping everlastingly at it can one become a master of the instrument."