CONTENTS

IV

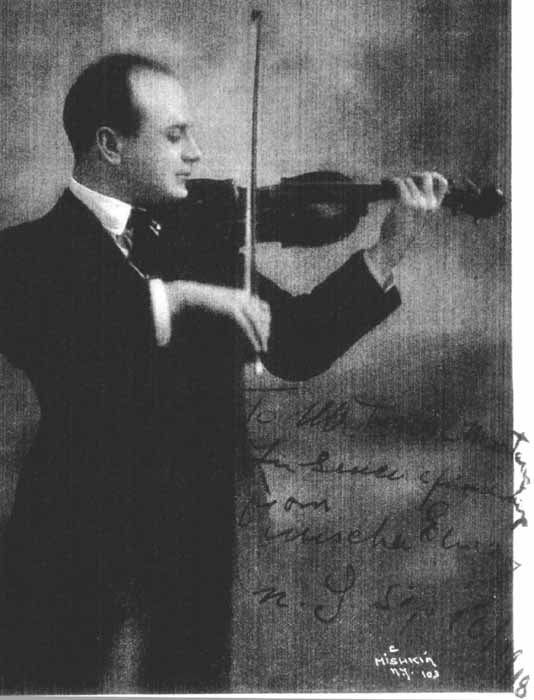

MISCHA ELMAN

LIFE AND COLOR IN INTERPRETATION.

TECHNICAL PHASES

To hear Mischa Elman on the concert platform,

to listen to him play, "with all that

wealth of tone, emotion and impulse which

places him in the very foremost rank of living

violinists," should be joy enough for any

music lover. To talk with him in his own

home, however, gives one a deeper insight into

his art as an interpreter; and in the pleasant

intimacy of familiar conversation the writer

learned much that the serious student of the

violin will be interested in knowing.

Mischa Elman

MANNERISMS IN PLAYING

We all know that Elman, when he plays in public, moves his head, moves his body, sways in time to the music; in a word there are certain mannerisms associated with his playing which critics have on occasion mentioned with grave suspicion, as evidences of sensationalism. Half fearing to insult him by asking whether he was "sincere," or whether his motions were "stage business" carefully rehearsed, as had been implied, I still ventured the question. He laughed boyishly and was evidently much amused.

"No, no," he said. "I do not study up any 'stage business' to help out my playing! I do not know whether I ought to compare myself to a dancer, but the appeal of the dance is in all musical movement. Certain rhythms and musical combinations affect me subconsciously. I suppose the direct influence of the music on me is such that there is a sort of emotional reflex: I move with the music in an unconscious translation of it into gesture. It is all so individual. The French violinists as a rule play very correctly in public, keeping their eye on finger and bow. And this appeals to me strongly in theory. In practice I seem to get away from it. It is a matter of temperament I presume. I am willing to believe I'm not graceful, but then—I do not know whether I move or do not move! Some of my friends have spoken of it to me at various times, so I suppose I do move, and sway and all the rest; but any movements of the sort must be unconscious, for I myself know nothing of them. And the idea that they are 'prepared' as 'stage effects' is delightful!" And again Elman laughed.

LIFE AND COLOR IN INTERPRETATION

"For that matter," he continued, "every real artist has some mannerisms when playing, I imagine. Yet more than mannerisms are needed to impress an American audience. Life and color in interpretation are the true secrets of great art. And beauty of interpretation depends, first of all, on variety of color. Technic is, after all, only secondary. No matter how well played a composition be, its performance must have color, nuance, movement, life! Each emotional mood of the moment must be fully expressed, and if it is its appeal is sure. I remember when I once played for Don Manuel, the young ex-king of Portugal, in London, I had an illustration of the fact. He was just a pathetic boy, very democratic, and personally very likable. He was somewhat neglected at the time, for it is well known and not altogether unnatural, that royalty securely established finds 'kings in exile' a bit embarrassing. Don Manuel was a music-lover, and especially fond of Bach. I had had long talks with the young king at various times, and my sympathies had been aroused in his behalf. On the evening of which I speak I played a Chopin Nocturne, and I know that into my playing there went some of my feeling for the pathos of the situation of this young stranger in a strange land, of my own age, eating the bitter bread of exile. When I had finished, the Marchioness of Ripon touched my arm: 'Look at the King!' she whispered. Don Manuel had been moved to tears.

"Of course the purely mechanical must always be dominated by the artistic personality of the player. Yet technic is also an important part of interpretation: knowing exactly how long to hold a bow, the most delicate inflections of its pressure on the strings. There must be perfect sympathy also with the composer's thought; his spirit must stand behind the personality of the artist. In the case of certain famous compositions, like the Beethoven concerto, for instance, this is so well established that the artist, and never the composer, is held responsible if it is not well played. But too rigorous an adherence to 'tradition' in playing is also an extreme. I once played privately for Joachim in Berlin: it was the Bach Chaconne. Now the edition I used was a standard one: and Joachim was extremely reverential as regards traditions. Yet he did not hesitate to indicate some changes which he thought should be made in the version of an authoritative edition, because 'they sounded better.' And 'How does it sound?' is really the true test of all interpretation."

ABSOLUTE PITCH THE FIRST ESSENTIAL OF A

PERFECTED TECHNIC

"What is the fundamental of a perfected violin technic?" was a natural question at this point. "Absolute pitch, first of all," replied Elman promptly. "Many a violinist plays a difficult passage, sounding every note; and yet it sounds out of tune. The first and second movements of the Beethoven concerto have no double-stops; yet they are extremely difficult to play. Why? Because they call for absolute pitch: they must be played in perfect tune so that each tone stands out in all its fullness and clarity like a rock in the sea. And without a fundamental control of pitch such a master work will always be beyond the violinist's reach. Many a player has the facility; but without perfect intonation he can never attain the highest perfection. On the other hand, any one who can play a single phrase in absolute pitch has the first and great essential. Few artists, not barring some of the greatest, play with perfect intonation. Its control depends first of all on the ear. And a sensitive ear finds differences and shading; it bids the violinist play a trifle sharper, a trifle flatter, according to the general harmonic color of the accompaniment; it leads him to observe a difference, when the harmonic atmosphere demands it, between a C sharp in the key of E major and a D flat in the same key.

TECHNICAL PHASES

"Every player finds some phases of technic easy and others difficult. For instance, I have never had to work hard for quality of tone—when I wish to get certain color effects they come: I have no difficulty in expressing my feelings, my emotions in tone. And in a technical way spiccato bowing, which many find so hard, has always been easy to me. I have never had to work for it. Double-stops, on the contrary, cost me hours of intensive work before I played them with ease and facility. What did I practice? Scales in double-stops—they give color and variety to tone. And I gave up a certain portion of my regular practice time to passages from concertos and sonatas. There is wonderful work in double-stops in the Ernst concerto and in the Paganini Études, for instance. With octaves and tenths I have never had any trouble: I have a broad hand and a wide stretch, which accounts for it, I suppose.

"Then there are harmonics, flageolets—I, have never been able to understand why they should be considered so difficult! They should not be white, colorless; but call for just as much color as any other tones (and any one who has heard Mischa Elman play harmonics knows that this is no mere theory on his part). I never think of harmonics as 'harmonics,' but try to give them just as much expressive quality as the notes of any other register. The mental attitude should influence their production—too many violinists think of them only as incidental to pyrotechnical display.

"And fingering? Fingering in general seems to me to be an individual matter. A concert artist may use a certain fingering for a certain passage which no pupil should use, and be entirely justified if he can thus secure a certain effect.

"I do not—speaking out of my own experience—believe much in methods: and never to the extent that they be allowed to kill the student's individuality. A clear, clean tone should always be the ideal of his striving. And to that end he must see that the up and down bows in a passage like the following from the Bach sonata in A minor (and Mr. Elman hastily jotted down the subjoined) are absolutely

even, and of the same length, played with the same strength and length of bow, otherwise the notes are swallowed. In light spiccato and staccato the detached notes should be played always with a single stroke of the bow. Some players, strange to say, find staccato notes more difficult to play at a moderate tempo than fast. I believe it to be altogether a matter of control—if proper control be there the tempo makes no difference. Wieniawski, I have read, could only play his staccati at a high rate of speed. Spiccato is generally held to be more difficult than staccato; yet I myself find it easier.

PROPORTION IN PRACTICE

"To influence a clear, singing tone with the left hand, to phrase it properly with the bow hand, is most important. And it is a matter of proportion. Good phrasing is spoiled by an ugly tone: a beautiful singing tone loses meaning if improperly phrased. When the student has reached a certain point of technical development, technic must be a secondary—yet not neglected—consideration, and he should devote himself to the production of a good tone. Many violinists have missed their career by exaggerated attention to either bow or violin hand. Both hands must be watched at the same time. And the question of proportion should always be kept in mind in practicing studies and passages: pressure of fingers and pressure of bow must be equalized, coordinated. The teacher can only do a certain amount: the pupil must do the rest.

AUER AS A TEACHER

"Take Auer for example. I may call myself the first real exponent of his school, in the sense of making his name widely known. Auer is a great teacher, and leaves much to the individuality of his pupils. He first heard me play at the Imperial Music School in Odessa, and took me to Petrograd to study with him, which I did for a year and four months. And he could accomplish wonders! That one year he had a little group of four pupils each one better than the other—a very stimulating situation for all of them. There was a magnetism about him: he literally hypnotized his pupils into doing better than their best—though in some cases it was evident that once the support of his magnetic personality was withdrawn, the pupil fell back into the level from which he had been raised for the time being.

"Yet Auer respected the fact that temperamentally I was not responsive to this form of appeal. He gave me of his best. I never practiced more than two or three hours a day—just enough to keep fresh. Often I came to my lesson unprepared, and he would have me play things—sonatas, concertos—which I had not touched for a year or more. He was a severe critic, but always a just one.

"I can recall how proud I was when he sent me to beautiful music-loving Helsingfors, in Finland—where all seems to be bloodshed and confusion now—to play a recital in his own stead on one occasion, and how proud he was of my success. Yet Auer had his little peculiarities. I have read somewhere that the great fencing-masters of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were very jealous of the secrets of their famous feints and ripostes, and only confided them to favorite pupils who promised not to reveal them. Auer had his little secrets, too, with which he was loth to part. When I was to make my début in Berlin, I remember, he was naturally enough interested—since I was his pupil—in my scoring a triumph. And he decided to part with some of his treasured technical thrusts and parries. And when I was going over the Tschaikovsky D minor concerto (which I was to play), he would select a passage and say: 'Now I'll play this for you. If you catch it, well and good; if not it is your own fault!' I am happy to say that I did not fail to 'catch' his meaning on any occasion. Auer really has a wonderful intellect, and some secrets well worth knowing. That he is so great an artist himself on the instrument is the more remarkable, since physically he was not exceptionally favored. Often, when he saw me, he'd say with a sigh: 'Ah, if I only had your hand!'

"Auer was a great virtuoso player. He held a unique place in the Imperial Ballet. You know in many of the celebrated ballets, Tschaikovsky's for instance, there occur beautiful and difficult solos for the violin. They call for an artist of the first rank, and Auer was accustomed to play them in Petrograd. In Russia it was considered a decided honor to be called upon to play one of those ballet solos; but in London it was looked on as something quite incidental. I remember when Diaghilev presented Tschaikovsky's Lac des Cygnes in London, the Grand-Duke Andrew Vladimirev (who had heard me play), an amiable young boy, and a patron of the arts, requested me—and at that time the request of a Romanov was still equivalent to a command—to play the violin solos which accompany the love scenes. It was not exactly easy, since I had to play and watch dancers and conductor at the same time. Yet it was a novelty for London, however; everybody was pleased and the Grand-Duke presented me with a handsome diamond pin as an acknowledgment.

VIOLIN MASTERY

"You ask me what I understand by 'Violin Mastery'? Well, it seems to me that the artist who can present anything he plays as a distinct picture, in every detail, framing the composer's idea in the perfect beauty of his plastic rendering, with absolute truth of color and proportion—he is the artist who deserves to be called a master!

"Of course, the instrument the artist uses is an important factor in making it possible for him to do his best. My violin? It is an authentic Strad—dated 1722. I bought it of Willy Burmester in London. You see he did not care much for it. The German style of playing is not calculated to bring out the tone beauty, the quality of the old Italian fiddles. I think Burmester had forced the tone, and it took me some time to make it mellow and truly responsive again, but now...." Mr. Elman beamed. It was evident he was satisfied with his instrument. "As to strings," he continued, "I never use wire strings—they have no color, no quality!

WHAT TO STUDY AND HOW

"For the advanced student there is a wealth of study material. No one ever wrote more beautiful violin music than Haendel, so rich in invention, in harmonic fullness. In Beethoven there are more ideas than tone—but such ideas! Schubert—all genuine, spontaneous! Bach is so gigantic that the violin often seems inadequate to express him. That is one reason why I do not play more Bach in public.

"The study of a sonata or concerto should entirely absorb the attention of the student to such a degree that, as he is able to play it, it has become a part of him. He should be able to play it as though it were an improvisation—of course without doing violence to the composer's idea. If he masters the composition in the way it should be mastered it becomes a portion of himself. Before I even take up my violin I study a piece thoroughly in score. I read and reread it until I am at home with the composer's thought, and its musical balance and proportion. Then, when I begin to play it, its salient points are already memorized, and the practicing gives me a kind of photographic reflex of detail. After I have not played a number for a long time it fades from my memory—like an old negative—but I need only go over it once or twice to have a clear mnemonic picture of it once more.

"Yes, I believe in transcriptions for the violin—with certain provisos," said Mr. Elman, in reply to another question. "First of all the music to be transcribed must lend itself naturally to the instrument. Almost any really good melodic line, especially a cantilena, will sound with a fitting harmonic development. Violinists of former days like Spohr, Rode and Paganini were more intent on composing music out of the violin! The modern idea lays stress first of all on the idea in music. In transcribing I try to forget I am a violinist, in order to form a perfect picture of the musical idea—its violinistic development must be a natural, subconscious working-out. If you will look at some of my recent transcripts—the Albaniz Tango, the negro melody Deep River and Amani's fine Orientale—you will see what I mean. They are conceived as pictures—I have not tried to analyze too much—and while so conceiving them their free harmonic background shapes itself for me without strain or effort.

A REMINISCENCE OF COLONNE

"Conductors with whom I have played? There are many: Hans Richter, who was a master of the baton; Nikisch, one of the greatest in conducting the orchestral accompaniment to a violin solo number; Colonne of Paris, and many others. I had an amusing experience with Colonne once. He brought his orchestra to Russia while I was with Auer, and was giving a concert at Pavlovsk, a summer resort near Petrograd. Colonne had a perfect horror of 'infant prodigies,' and Auer had arranged for me to play with his orchestra without telling him my age—I was eleven at the time. When Colonne saw me, violin in hand, ready to step on the stage, he drew himself up and said with emphasis: 'I play with a prodigy! Never!' Nothing could move him, and I had to play to a piano accompaniment. After he had heard me play, though, he came over to me and said: 'The best apology I can make for what I said is to ask you to do me the honor of playing with the Orchestre Colonne in Paris.' He was as good as his word. Four months later I went to Paris and played the Mendelssohn concerto for him with great success."