CONTENTS

XIV

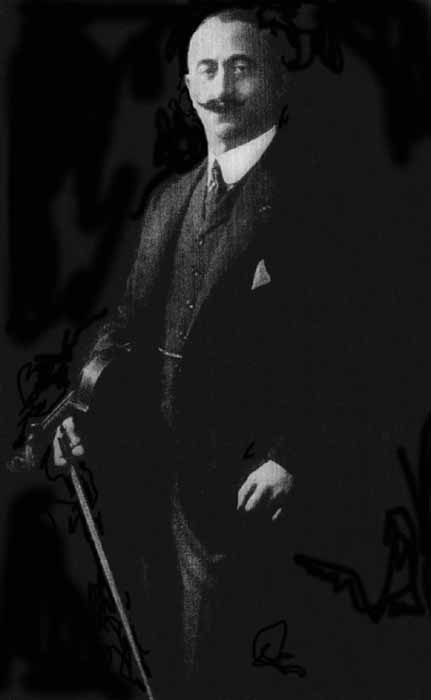

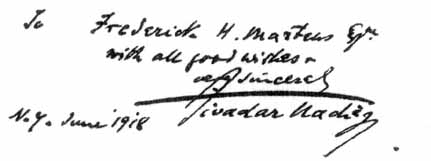

TIVADAR NACHÉZ

JOACHIM AND LÉONARD AS TEACHERS

Tivadar Nachéz, the celebrated violin

virtuoso, is better known as a concertizing

artist in Europe, where he has played with all

the leading symphonic orchestras, than in this

country, to which he paid his first visit during

these times of war, and which he was about

to leave for his London home when the writer

had the pleasure of meeting him. Yet, though

he has not appeared in public in this country

(if we except some Red Cross concerts in California,

at which he gave his auditors of his

best to further our noblest war charity), his

name is familiar to every violinist. For is not

Mr. Nachéz the composer of the "Gypsy

Dances" for violin and piano, which have made

him famous?

Genuinely musical, effective and largely successful as they have been, however, as any one who has played them can testify, the composer of the "Gypsy Dances" regards them with mixed feelings. "I have done other work that seems to me, relatively, much more important," said Mr. Nachéz, "but when my name happens to be mentioned, echo always answers 'Gypsy Dances,' my little rubbishy 'Gypsy Dances!' It is not quite fair. I have published thirty-five works, among them a 'Requiem Mass,' an orchestral overture, two violin concertos, three rhapsodies for violin and orchestra, variations on a Swiss theme, Romances, a Polonaise (dedicated to Ysaye), and Evening Song, three Poèmes hongrois, twelve classical masterworks of the 17th century—to say nothing of songs, etc.—and the two concertos of Vivaldi and Nardini which I have edited, practically new creations, owing to the addition of the piano accompaniments and orchestral score. I wrote the 'Gypsy Dances' as a mere boy when I was studying with H. Léonard in Paris, and really at his suggestion. In one of my lessons I played Sarasate's 'Spanish Dances,' which chanced to be published at the time, and at once made a great hit. So Léonard said to me: 'Why not write some Hungarian Gypsy dances—there must be wonderful material at hand in the music of the Tziganes of Hungary. You should do something with it!' I took him at his word, and he liked my 'Dances' so well that he made me play them at his musical evenings, which he gave often during the winter, and which were always attended by the musical Tout Paris! I may say that during these last thirty years there has been scarcely a violinist before the public who at one time or the other has not played these 'Gypsy Dances.' Besides the original edition, there are two (pirated!) editions in America and six in Europe.

Tivadar Nachéz

THE BEGINNING OF A VIOLINISTIC CAREER:

PLAYING WITH LISZT

"No, Léonard was not my first teacher. I took up violin work when a boy of five years of age, and for seven years practiced from eight to ten hours a day, studying with Sabathiel, the leader of the Royal Orchestra in Budapest, where I was born, though England, the land of my adoption, in which I have lived these last twenty-six years, is the land where I have found all my happiness, and much gratifying honor, and of which I have been a devoted, ardent and loyal naturalized citizen for more than a quarter of a century. Sabathiel was an excellent routine teacher, and grounded me well in the fundamentals—good tone production and technical control. Later I had far greater teachers, and they taught me much, but—in the last analysis, most of the little I have achieved I owe to myself, to hard, untiring work: I had determined to be a violinist and I trust I became one. No serious student of the instrument should ever forget that, no matter who his teacher may be, he himself must supply the determination, the continued energy and devotion which will lead him to success.

"Playing with Liszt—he was an intimate friend of my father—is my most precious musical recollection of Budapest. I enjoyed it a great deal more than my regular lesson work. He would condescend to play with me some evenings and you can imagine what rare musical enjoyment, what happiness there was in playing with such a genius! I was still a boy when with him I played the Grieg F major sonata, which had just come fresh from the press. He played with me the D minor sonata of Schumann and introduced me to the mystic beauties of the Beethoven sonatas. I can still recall how in the Beethoven C minor sonata, in the first movement, Liszt would bring out a certain broken chromatic passage in the left hand, with a mighty crescendo, an effect of melodious thunder, of enormous depth of tone, and yet with the most exquisite regard for the balance between the violin and his own instrument. And there was not a trace of condescension in his attitude toward me; but always encouragement, a tender affectionate and paternal interest in a young boy, who at that moment was a brother artist.

"Through Liszt I came to know the great men of Hungarian music of that time: Erkel, Hans Richter, Robert Volkmann, Count Geza Zichy, and eventually I secured a scholarship, which the King had founded for music, to study with Joachim in Berlin, where I remained nearly three years. Hubay was my companion there; but afterward we separated, he going to Vieuxtemps, while I went to Léonard.

JOACHIM AS A TEACHER AND INTERPRETER

"Joachim was, perhaps, the most celebrated teacher of his time. Yet it is one of the greatest ironies of fate that when he died there was not one of his pupils who was considered by the German authorities 'great' enough to take the place the Master had held. Henri Marteau, who was not his pupil, and did not even exemplify his style in playing, was chosen to succeed him! Henri Petri, a Vieuxtemps pupil who went to Joachim, played just as well when he came to him as when he left him. The same might be said of Willy Burmester, Hess, Kes and Halir, the latter one of those Bohemian artists who had a tremendous 'Kubelik-like' execution. Teaching is and always will be a special gift. There are many minor artists who are wonderful 'teachers,' and vice versa!

"Yet if Joachim may be criticized as regards the way of imparting the secrets of technical phases in his violin teaching, as a teacher of interpretation he was incomparable! As an interpreter of Beethoven and of Bach in particular, there has never been any one to equal Joachim. Yet he never played the same Bach composition twice in the same way. We were four in our class, and Hubay and I used to bring our copies of the sonatas with us, to make marginal notes while Joachim played to us, and these instantaneous musical 'snapshots' remain very interesting. But no matter how Joachim played Bach, it was always with a big tone, broad chords of an organ-like effect. There is no greater discrepancy than the edition of the Bach sonatas published (since his death) by Moser, and which is supposed to embody Joachim's interpretation. Sweeping chords, which Joachim always played with the utmost breadth, are 'arpeggiated' in Moser's edition! Why, if any of his pupils had ever attempted to play, for instance, the end of the Bourée in the B minor Partita of Bach à la Moser, Joachim would have broken his bow over their heads!

STUDYING WITH LÉONARD

"After three years' study I left Joachim and went to Paris. Liszt had given me letters of introduction to various French artists, among them Saint-Saëns. One evening I happened to hear Léonard play Corelli's La Folia in the Salle Pleyel, and the liquid clarity and beauty of his tone so impressed me that I decided I must study with him. I played for him and he accepted me as a pupil. I am free to admit that my tone, which people seem to be pleased to praise especially, I owe entirely to Léonard, for when I came to him I had the so-called 'German tone' (son allemand), of a harsh, rasping quality, which I tried to abandon absolutely. Léonard often would point to his ears while teaching and say: 'Ouvrez vos oreilles: écoutéz la beauté du son!' ('Open your ears, listen for beauty of sound!'). Most Joachim pupils you hear (unless they have reformed) attack a chord with the nut of the bow, the German method, which unduly stresses the attack. Léonard, on the contrary, insisted with his pupils on the attack being made with such smoothness as to be absolutely unobtrusive. Being a nephew of Mme. Malibran, he attached special importance to the 'singing' tone, and advised his pupils to hear great singers, to listen to them, and to try and reproduce their bel canto on the violin.

"He was most particular in his observance of every nuance of shading and expression. He told me that when he played Mendelssohn's concerto (for the first time) at the Leipsic Gewandhaus, at a rehearsal, Mendelssohn himself conducting, he began the first phrase with a full mezzo-forte tone. Mendelssohn laid his hand on his arm and said: 'But it begins piano!' In reply Léonard merely pointed with his bow to the score—the p which is now indicated in all editions had been omitted by some printer's error, and he had been quite within his rights in playing mezzo-forte.

"Léonard paid a great deal of attention to scales and the right way to practice them. He would say, 'Il faut filer les sons: c'est l'art des maîtres. ('One must spin out the tone: that is the art of the masters.') He taught his pupils to play the scales with long, steady bowings, counting sixty to each bow. Himself a great classical violinist, he nevertheless paid a good deal of attention to virtuoso pieces; and always tried to prepare his pupils for public life. He had all sorts of wise hints for the budding concert artist, and was in the habit of saying: 'You must plan a program as you would the ménu of a dinner: there should be something for every one's taste. And, especially, if you are playing on a long program, together with other artists, offer nothing indigestible—let your number be a relief!'

SIVORI

"While studying with Léonard I met Sivori, Paganini's only pupil (if we except Catarina Caleagno), for whom Paganini wrote a concerto and six short sonatas. Léonard took me to see him late one evening at the Hôtel de Havane in Paris, where Sivori was staying. When we came to his room we heard the sound of slow scales, beautifully played, coming from behind the closed door. We peered through the keyhole, and there he sat on his bed stringing his scale tones like pearls. He was a little chap and had the tiniest hands I have ever seen. Was this a drawback? If so, no one could tell from his playing; he had a flawless technic, and a really pearly quality of tone. He was very jolly and amiable, and he and Léonard were great friends, each always going to hear the other whenever he played in concert. My four years in Paris were in the main years of storm and stress—plain living and hard, very hard, concentrated work. I gave some accompanying lessons to help keep things going. When I left Paris I went to London and then began my public life as a concert violinist.

GREAT MOMENTS IN AN ARTIST'S LIFE

"What is the happiest remembrance of my career as a virtuoso? Some of the great moments in my life as an artist? It is hard to say. Of course some of my court appearances before the crowned heads of Europe are dear to me, not so much because they were court appearances, but because of the graciousness and appreciation of the highly placed personages for whom I played.

"Then, what I count a signal honor, I have played no less than three times as a solo artist with the Royal Philharmonic Society of London, the oldest symphonic society in Europe, for whom Beethoven composed his immortal IXth symphony (once under Sir Arthur Sullivan's baton; once under that of Sir A.C. Mackenzie, and once with Sir Frederick Cowen as conductor—on this last occasion I was asked to introduce my new Second concerto in B minor, Op. 36, at the time still in ms.) Then there is quite a number of great conductors with whom I have appeared, a few among them being Liszt, Rubinstein, Brahms, Pasdeloup, Sir August Manns, Sir Charles Hallé, L. Mancinelli, Weingartner and Hans Richter, etc. Perhaps, as a violinist, what I like best to recall is that as a boy I was invited by Richter to go with him to Bayreuth and play at the foundation of the Bayreuth festival theater, which however my parents would not permit owing to my tender age. I also remember with pleasure an episode at the famous Pasdeloup Concerts in the Cirque d'hiver in Paris, on an occasion when I performed the F sharp minor concerto of Ernst. After I had finished, two ladies came to the green room: they were in deep mourning, and one of them greatly moved, asked me to 'allow her to thank me' for the manner in which I had played this concerto—she said: 'I am the widow of Ernst!' She also told me that since his death she had never heard the concerto played as I had played it! In presenting to me her companion, the Marquise de Gallifet (wife of the General de Gallifet who led the brigade of the Chasseurs d'Afrique in the heroic charge of General Margueritte's cavalry division at Sedan, which excited the admiration of the old king of Prussia), I had the honor of meeting the once world famous violinist Mlle. Millanollo, as she was before her marriage. Mme. Ernst often came to hear me play her late husband's music, and as a parting gift presented me with his beautiful 'Tourte' bow, and an autographed copy of the first edition of Ernst's transcription for solo violin of Schubert's 'Erlking.' It is so incredibly difficult to play with proper balance of melody and accompaniment—I never heard any one but Kubelik play it—that it is almost impossible. It is so difficult, in fact, that it should not be played!

VIOLINS AND STRINGS: SARASATE

"My violin? I am a Stradivarius player, and possess two fine Strads, though I also have a beautiful Joseph Guarnerius. Ysaye, Thibaud and Caressa, when they lunched with me not long ago, were enthusiastic about them. My favorite Strad is a 1716 instrument—I have used it for twenty-five years. But I cannot use the wire strings that are now in such vogue here. I have to have Italian gut strings. The wire E cuts my fingers, and besides I notice a perceptible difference in sound quality. Of course, wire strings are practical; they do not 'snap' on the concert stage. Speaking of strings that 'snap,' reminds me that the first time I heard Sarasate play the Saint-Saëns concerto, at Frankfort, he twice forgot his place and stopped. They brought him the music, he began for the third time and then—the E string snapped! I do not think any other than Sarasate could have carried off these successive mishaps and brought his concert to a triumphant conclusion. He was a great friend of mine and one of the most perfect players I have ever known, as well as one of the greatest grand seigneurs among violinists. His rendering of romantic works, Saint-Saëns, Lalo, Bruch, was exquisite—I have never, never heard them played as beautifully. On the other hand, his Bach playing was excruciating—he played Bach sonatas as though they were virtuoso pieces. It made one think of Hans von Bülow's mot when, in speaking of a certain famous pianist, he said: 'He plays Beethoven with velocity and Czerny with expression.' But to hear Sarasate play romantic music, his own 'Spanish Dances' for instance, was all like glorious birdsong and golden sunshine, a lark soaring heavenwards!

THE NARDINI CONCERTO IN A

"You ask about my compositions? Well, Eddy Brown is going to play my Second violin concerto, Op. 36 in B flat, which I wrote for the London Philharmonic Society, next season; Elman the Nardini concerto in A, which was published only shortly before the outbreak of the war. Thirty years ago I found, by chance, three old Nardini concertos for violin and bass in the composer's original ms., in Bologna. The best was the one in A—a beautiful work! But the bass was not even figured, and the task of reconstructing the accompaniment for piano, as well as for orchestra, and reverently doing justice to the composer's original intent and idea; while at the same time making its beauties clearly and expressively available from the standpoint of the violinist of to-day, was not easy. Still, I think I may say I succeeded." And Mr. Nachéz showed me some letters from famous contemporaries who had made the acquaintance of this Nardini concerto in A major. Auer, Thibaud, Sir Hubert Parry (who said that he had "infused the work with new life"), Pollak, Switzerland's ranking fiddler, Carl Flesch, author of the well-known Urstudien—all expressed their admiration. One we cannot forbear quoting a letter in part. It was from Ottokar Sevčik. The great Bohemian pedagogue is usually regarded as the apostle of mechanism in violin playing: as the inventor of an inexorably logical system of development, which stresses the technical at the expense of the musical. The following lines show him in quite a different light:

"I would not be surprised if Nardini, Vivaldi and their companions were to appear to you at the midnight hour in order to thank the master for having given new life to their works, long buried beneath the mold of figured basses; works whose vital, pulsating possibilities these old gentlemen probably never suspected. Nardini emerges from your alchemistic musical laboratory with so fresh and lively a quality of charm that starving fiddlers will greet him with the same pleasure with which the bee greets the first honeyed blossom of spring."

VIOLIN MASTERY

"And now you want my definition of 'Violin Mastery'? To me the whole art of playing violin is contained in the reverent and respectful interpretation of the works of the great masters. I consider the artist only their messenger, singing the message they give us. And the more one realizes this, the greater becomes one's veneration especially for Bach's creative work. For twenty years I never failed to play the Bach solo sonatas for violin every day of my life—a violinist's 'daily prayer' in its truest sense! Students of Bach are apt, in the beginning, to play, say, the finale of the G minor sonata, the final Allegro of the A minor sonata, the Gigue of the B minor, or the Preludio of the E major sonata like a mechanical exercise: it takes constant study to disclose their intimate harmonic melodious conception and poetry! One should always remember that technic is, after all, only a means. It must be acquired in order to be an unhampered master of the instrument, as a medium for presenting the thoughts of the great creators—but these thoughts, and not their medium of expression, are the chief objects of the true and great artist, whose aim in life is to serve his Art humbly, reverently and faithfully! You remember these words:

"'In the very torrent, tempest, and, as I may say, the whirlwind of passion, you must acquire and beget a temperance that may give it smoothness. Oh, it offends me to the soul to hear a robustious, periwig-pated fellow tear a passion to tatters, to very rags, to split the ears of the groundlings, who for the most part are capable of nothing but inexplicable dumbshows and noise!...'"