CONTENTS

XXII

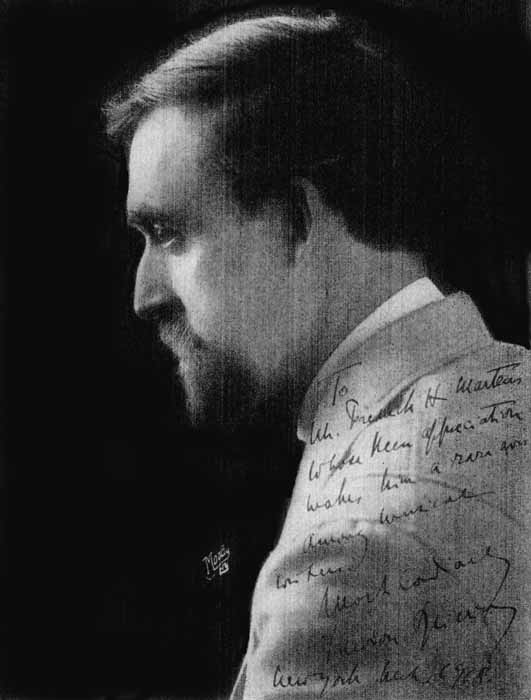

THEODORE SPIERING

THE APPLICATION OF BOW EXERCISES TO

THE STUDY OF KREUTZER

A. Walter Kramer has said: "Mr. Spiering

knows how serious a study can be made of

the violin, because he has made it. He has investigated

the 'how' and 'why' of every detail,

and what he has to say about the violin is the

utterance of a big musician, one who has mastered

the instrument." And Theodore Spiering,

solo artist and conductor, as a teacher has

that wider horizon which has justified the

statement made that "he is animated by the

thoughts and ideals which stimulate a Godowsky

or Busoni." Such being the case, it was

with unmixed satisfaction that the writer found

Mr. Spiering willing to give him the benefit

of some of those constructive ideas of his as regards

violin study which have established his

reputation so prominently in that field.

TWO TYPES OF STUDENTS

"There are certain underlying principles which govern every detail of the violinist's Art," said Mr. Spiering, "and unless the violinist fully appreciates their significance, and has the intelligence and patience to apply them in everything he does, he will never achieve that absolute command over his instrument which mastery implies.

"It is a peculiar fact that a large percentage of students—probably believing that they can reach their goal by a short cut—resent the mental effort required to master these principles, the passive resistance, evident in their work, preventing them from deriving true benefit from their studies. They form that large class which learns merely by imitation, and invariably retrograde the moment they are no longer under the teacher's supervision.

"The smaller group, with an analytical bent of mind, largely subject themselves to the needed mental drill and thus provide for themselves that inestimable basic quality that makes them independent and capable of developing their talent to its full fruition.

Theodore Spiering

MENTAL AND PHYSICAL PROCESSES COÖRDINATED

"The conventional manner of teaching provided an inordinate number of mechanical exercises in order to overcome so called 'technical difficulties.' Only the prima facie disturbance, however, was thus taken into consideration—not its actual cause. The result was, that notwithstanding the great amount of labor thus expended, the effort had to be repeated each time the problem was confronted. Aside from the obviously uncertain results secured in this manner, it meant deadening of the imagination and cramping of interpretative possibilities. It is only possible to reduce to a minimum the element of chance by scrupulously carrying out the dictates of the laws governing vital principles. Analysis and the severest self-criticism are the means of determination as to whether theory and practice conform with one another.

"Mental preparedness (Marcus Aurelius calls it 'the good ordering of the mind') is the keynote of technical control. Together with the principle of relaxation it provides the player with the most effective means of establishing precise and sensitive coöperation between mental and physical processes. Muscular relaxation at will is one of the results of this coöperation. It makes sustained effort possible (counteracting the contraction ordinarily resulting therefrom), and it is freedom of movement more than anything else that tends to establish confidence.

THE TWO-FOLD VALUE OF CELEBRATED STUDY WORKS

"The study period of the average American is limited. It has been growing less year by year. Hence the teacher has had to redouble his efforts. The desire to give my pupils the essentials of technical control in their most concentrated and immediately applicable form, have led me to evolve a series of 'bow exercises,' which, however, do not merely pursue a mechanical purpose. Primarily enforcing the carrying out of basic principles as pertaining to the bow—and establishing or correcting (as the case may be) arm and hand (right arm) positions, they supply the means of creating a larger interpretative style.

"I use the Kreutzer studies as the medium of these bow-exercises, since the application of new technical ideas is easier when the music itself is familiar to the student. I have a two-fold object in mind when I review these studies in my particular manner, technic and appreciation. I might add that not only Kreutzer, but Fiorillo and Rode—in fact all the celebrated 'Caprices,' with the possible exception of those of Paganini—are viewed almost entirely from the purely technical side, as belonging to the classroom, because their musical qualities have not been sufficiently pointed out. Rode, in particular, is a veritable musical treasure trove.

THE APPLICATION OF BOW EXERCISES

TO THE STUDY OF KREUTZER

"How do I use the Kreutzer studies to develop style and technic? By making the student study them in such wise that the following principles are emphasized in his work: control before action (mental direction at all times); relaxation; and observance of string levels; for unimpeded movement is more important than pressure as regards the carrying tone. These principles are among the most important pertaining to right arm technic.

"In Study No. 2 (version 1, up-strokes only, version 2, down-strokes only), I have my pupils use the full arm stroke (grand detaché). In version 1, the bow is taken from the string after completion of stroke—but in such a way that the vibrations of the string are not interfered with. Complete relaxation is insured by release of the thumb—the bow being caught in a casual manner, third and fourth fingers slipping from their normal position on stick—and holding, but not tightly clasping, the bow.

"Version 2 calls for a return down-stroke, the return part of the stroke being accomplished over the string, but making no division in stroke, no hesitating before the return. Relaxation is secured as before. Rapidity of stroke, elimination of impediment (faulty hand or arm position and unnecessary upper arm action), is the aim of this exercise. The pause between each stroke—caused by relinquishing the hold on the bow—reminds the student that mental control should at all times be paramount: that analysis of technical detail is of vital importance.

"In Study No. 7 I employ the same vigorous full arm strokes as in No. 2: the up and down bows as indicated in the original version. The bow is raised from the strings after each note, by means of hand (little finger, first and thumb) not by arm action. Normal hand position is retained: thumb not released.

"The observance of string levels is very essential. While the stroke is in progress the arm must not leave its level in an anticipatory movement to reach the next level. Especially after the down-stroke is it advisable to verify the arm position with regard to this feature.

"No. 8 affords opportunity for a résumé of the work done in Nos. 2 and 7:

"It is evident that the tempo of this study must be very much reduced in speed. The return down-stroke as in No. 2: the second down-stroke as in No. 7: the up-strokes as in No. 2.

"In Study No. 5 I use the hand-stroke only—at the frog—arm absolutely immobile, with no attempt at tone. This exercise represents the first attempt at dissecting the martelé idea: precise timing of pressure, movement (stroke), and relaxation. The pause between the strokes is utilized to learn the value of left hand preparedness, with the fingers in place before bow action.

"In Study No. 13 I develop the principles of string crossing, of the extension stroke, and articulation. String crossing is the main feature of the exercise. I employ three versions, in order to accomplish my aim. In version 1 I consider only the crossing from a higher to a lower level:

version 2:

version 3 is the original version. In versions 1 and 2 I omit all repetitions:

Articulation is one of the main points at issue—the middle note is generally inarticulate. For further string crossing analysis I use Kreutzer's No. 25. Study No. 10 I carry out as a martelé study, with the string crossing very much in evidence; establishing observance of the notes occurring on the same string level, consequently compelling a more judicious use of the so-called wrist movement (not merely developing a supple wrist, with indefinite crossing movements, which in many cases are applied by the player without regard to actual string crossing) and in consequence securing stability of bow on string when string level is not changed, this result being secured even in rapid passage work.

"In Studies 11, 19 and 21 I cover shifting and left thumb action: in No. 9, finger action—flexibility and evenness, the left thumb relaxed—the fundamental idea of the trill. After the interrupted types of bowing (grand detaché, martelé, staccato) have been carefully studied, the continuous types (detaché, legato and spiccato) are then taken up, and in part the same studies again used: 2, 7, 8. Lastly the slurred legato comes under consideration (Studies 9, 11, 14, 22, 27, 29). Shifting, extension and string crossing have all been previously considered, and hence the legato should be allowed to take its even course.

"Although I do, temporarily, place these studies on a purely mechanical level, I am convinced that they thus serve to call into being a broader musical appreciation for the whole set. For I have found that in spite of the fact that pupils who come to me have all played their Kreutzer, with very few exceptions have they realized the musical message which it contains. The time when the student body will have learned to depict successfully musical character—even in studies and caprices—will mark the fulfillment of the teacher's task with regard to the cultivation of the right arm—which is essentially the teacher's domain.

SOME OF MR. SPIERING'S OWN STUDY SOUVENIRS

"It may interest you to know," Mr. Spiering said in reply to a question, "that I began my teaching career in Chicago immediately following my four years with Joachim in Berlin. It was natural that I should first commit myself to the pedagogic methods of the Hochschule, which to a great extent, however, I discarded as my own views crystallized. I found that too much emphasis allotted the wrist stroke (a misnomer, by the way), was bound to result in too academic a style. By transferring primary importance to the control of the full arm-stroke—with the hand-stroke incidentally completing the control—I felt that I was better able to reflect the larger interpretative ideals which my years of musical development were creating for me. Chamber music—a youthful passion—led me to interest myself in symphonic work and conducting. These activities not only reacted favorably on my solo playing, but influenced my development as regards the broader, more dramatic style, the grand manner in interpretation. It is this realization that places me in a position to earnestly advise the ambitious student not to disregard the great artistic benefits to be derived from the cultivation of chamber music and symphonic playing.

"I might call my teaching ideals a combination of those of the Franco-Belgian and German schools. To the former I attribute my preference for the large sweep of the bow-arm, its style and tonal superiority; to the latter, vigor of interpretation and attention to musical detail.

VIOLIN MASTERY

"How do I define 'Violin Mastery'? The violinist who has succeeded in eliminating all superfluous tension or physical resistance, whose mental control is such that the technic of the left hand and right arm has become coordinate, thus forming a perfect mechanism not working at cross-purposes; who, furthermore, is so well poised that he never oversteps the boundaries of good taste in his interpretations, though vitally alive to the human element; who, finally, has so broad an outlook on life and Art that he is able to reveal the transcendent spirit characterizing the works of the great masters—such a violinist has truly attained mastery!"