CONTENTS

XVI

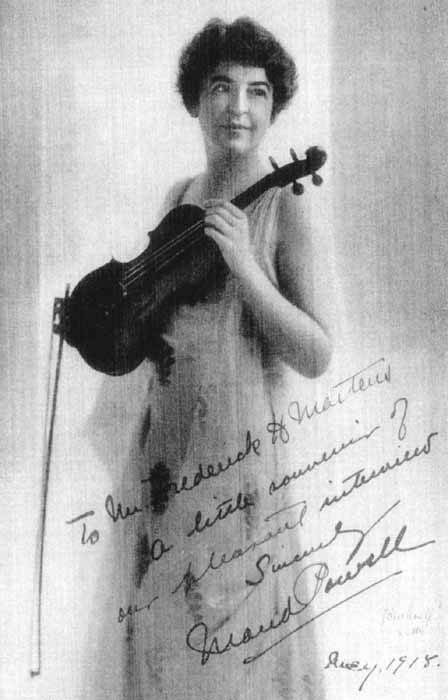

MAUD POWELL

TECHNICAL DIFFICULTIES: SOME HINTS

FOR THE CONCERT PLAYER

Maud Powell is often alluded to as our

representative "American woman violinist"

which, while true in a narrower sense, is not altogether

just in a broader way. It would be

decidedly more fair to consider her a representative

American violinist, without stressing

the term "woman"; for as regards Art in its

higher sense, the artist comes first, sex being

incidental, and Maud Powell is first and foremost—an

artist. And her infinite capacity for

taking pains, her willingness to work hard

have had no small part in the position she

has made for herself, and the success she has

achieved.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF A CONCERT VIOLINIST

"Too many Americans who take up the violin professionally," Maud Powell told the writer, "do not realize that the mastery of the instrument is a life study, that without hard, concentrated work they cannot reach the higher levels of their art. Then, too, they are too often inclined to think that if they have a good tone and technic that this is all they need. They forget that the musical instinct must be cultivated; they do not attach enough importance to musical surroundings: to hearing and understanding music of every kind, not only that written for the violin. They do not realize the value of ensemble work and its influence as an educational factor of the greatest artistic value. I remember when I was a girl of eight, my mother used to play the Mozart violin sonatas with me; I heard all the music I possibly could hear; I was taught harmony and musical form in direct connection with my practical work, so that theory was a living thing to me and no abstraction. In my home town I played in an orchestra of twenty pieces—Oh, no, not a 'ladies orchestra'—the other members were men grown! I played chamber music as well as solos whenever the opportunity offered, at home and in public. In fact music was part of my life.

Maud Powell

"No student who looks on music primarily as a thing apart in his existence, as a bread-winning tool, as a craft rather than an art, can ever mount to the high places. So often girls [who sometimes lack the practical vision of boys], although having studied but a few years, come to me and say: 'My one ambition is to become a great virtuoso on the violin! I want to begin to study the great concertos!' And I have to tell them that their first ambition should be to become musicians—to study, to know, to understand music before they venture on its interpretation. Virtuosity without musicianship will not carry one far these days. In many cases these students come from small inland towns, far from any music center, and have a wrong attitude of mind. They crave the glamor of footlights, flowers and applause, not realizing that music is a speech, an idiom, which they must master in order to interpret the works of the great composers.

THE INFLUENCE OF THE TEACHER

"Of course, all artistic playing represents essentially the mental control of technical means. But to acquire the latter in the right way, while at the same time developing the former, calls for the best of teachers. The problem of the teacher is to prevent his pupils from being too imitative—all students are natural imitators—and furthering the quality of musical imagination in them. Pupils generally have something of the teacher's tone—Auer pupils have the Auer tone, Joachim pupils have a Joachim tone, an excellent thing. But as each pupil has an individuality of his own, he should never sink it altogether in that of his teacher. It is this imitative trend which often makes it hard to judge a young player's work. I was very fortunate in my teachers. William Lewis of Chicago gave me a splendid start. Then I studied in turn with Schradieck in Leipsic—Schradieck himself was a pupil of Ferdinand David and of Léonard—Joachim in Berlin, and Charles Dancla in Paris. I might say that I owe most, in a way, to William Lewis, a born fiddler. Of my three European masters Dancla was unquestionably the greatest as a teacher—of course I am speaking for myself. It was no doubt an advantage, a decided advantage for me in my artistic development, which was slow—a family trait—to enjoy the broadening experience of three entirely different styles of teaching, and to be able to assimilate the best of each. Yet Joachim was a far greater violinist than teacher. His method was a cramping one, owing to his insistence on pouring all his pupils into the same mold, so to speak, of forming them all on the Joachim lathe. But Dancla was inspiring. He taught me De Bériot's wonderful method of attack; he showed me how to develop purity of style. Dancla's method of teaching gave his pupils a technical equipment which carried bowing right along, 'neck and neck' with the finger work of the left hand, while the Germans are apt to stress finger development at the expense of the bow. And without ever neglecting technical means, Dancla always put the purely musical before the purely virtuoso side of playing. And this is always a sign of a good teacher. He was unsparing in taking pains and very fair.

"I remember that I was passed first in a class of eighty-four at an examination, after only three private lessons in which to prepare the concerto movement to be played. I was surprised and asked him why Mlle.—— who, it seemed to me, had played better than I, had not passed. 'Ah,' he said, 'Mlle.—— studied that movement for six months; and in comparison, you, with only three lessons, play it better!' Dancla switched me right over in his teaching from German to French methods, and taught me how to become an artist, just as I had learned in Germany to become a musician. The French school has taste, elegance, imagination; the German is more conservative, serious, and has, perhaps, more depth.

TECHNICAL DIFFICULTIES

"Perhaps it is because I belong to an older school, or it may be because I laid stress on technic because of its necessity as a means of expression—at any rate I worked hard at it. Naturally, one should never practice any technical difficulty too long at a stretch. Young players sometimes forget this. I know that staccato playing was not easy for me at one time. I believe a real staccato is inborn; a knack. I used to grumble about it to Joachim and he told me once that musically staccato did not have much value. His own, by the way, was very labored and heavy. He admitted that he had none. Wieniawski had such a wonderful staccato that one finds much of it in his music. When I first began to play his D minor concerto I simply made up my mind to get a staccato. It came in time, by sheer force of will. After that I had no trouble. An artistic staccato should, like the trill, be plastic and under control; for different schools of composition demand different styles of treatment of such details.

"Octaves—the unison, not broken—I did not find difficult; but though they are supposed to add volume of tone they sound hideous to me. I have used them in certain passages of my arrangement of 'Deep River,' but when I heard them played, promised myself I would never repeat the experiment. Wilhelmj has committed even a worse crime in taste by putting six long bars of Schubert's lovely Ave Maria in octaves. Of course they represent skill; but I think they are only justified in show pieces. Harmonics I always found easy; though whether they ring out as they should always depends more or less on atmospheric conditions, the strings and the amount of rosin on the bow. On the concert stage if the player stands in a draught the harmonics are sometimes husky.

THE AMERICAN WOMAN VIOLINIST AND AMERICAN MUSIC

"The old days of virtuoso 'tricks' have passed—I should like to hope forever. Not that some of the old type virtuosos were not fine players. Remenyi played beautifully. So did Ole Bull. I remember one favorite trick of the latter's, for instance, which would hardly pass muster to-day. I have seen him draw out a long pp, the audience listening breathlessly, while he drew his bow way beyond the string, and then looked innocently at the point of the bow, as though wondering where the tone had vanished. It invariably brought down the house.

"Yet an artist must be a virtuoso in the modern sense to do his full duty. And here in America that duty is to help those who are groping for something higher and better musically; to help without rebuffing them. When I first began my career as a concert violinist I did pioneer work for the cause of the American woman violinist, going on with the work begun by Mme. Camilla Urso. A strong prejudice then existed against women fiddlers, which even yet has not altogether been overcome. The very fact that a Western manager recently told Mr. Turner with surprise that he 'had made a success of a woman artist' proves it. When I first began to play here in concert this prejudice was much stronger. Yet I kept on and secured engagements to play with orchestra at a time when they were difficult to obtain. Theodore Thomas liked my playing (he said I had brains), and it was with his orchestra that I introduced the concertos of Saint-Saëns (C min.), Lalo (F min.), and others, to American audiences.

"The fact that I realized that my sex was against me in a way led me to be startlingly authoritative and convincing in the masculine manner when I first played. This is a mistake no woman violinist should make. And from the moment that James Huneker wrote that I 'was not developing the feminine side of my work,' I determined to be just myself, and play as the spirit moved me, with no further thought of sex or sex distinctions which, in Art, after all, are secondary. I never realized this more forcibly than once, when, sitting as a judge, I listened to the competitive playing of a number of young professional violinists and pianists. The individual performers, unseen by the judges, played in turn behind a screen. And in three cases my fellow judges and myself guessed wrongly with regard to the sex of the players. When we thought we had heard a young man play it happened to be a young woman, and vice versa.

"To return to the question of concert-work. You must not think that I have played only foreign music in public. I have always believed in American composers and in American composition, and as an American have tried to do justice as an interpreting artist to the music of my native land. Aside from the violin concertos by Harry Rowe Shelly and Henry Holden Huss, I have played any number of shorter original compositions by such representative American composers as Arthur Foote, Mrs. H.H.A. Beach, Victor Herbert, John Philip Sousa, Arthur Bird, Edwin Grasse, Marion Bauer, Cecil Burleigh, Harry Gilbert, A. Walter Kramer, Grace White, Charles Wakefield Cadman and others. Then, too, I have presented transcriptions by Arthur Hartmann, Francis Macmillan and Sol Marcosson, as well as some of my own. Transcriptions are wrong, theoretically; yet some songs, like Rimsky-Korsakov's 'Song of India' and some piano pieces, like the Dvořák Humoresque, are so obviously effective on the violin that a transcription justifies itself. My latest temptative in that direction is my 'Four American Folk Songs,' a simple setting of four well-known airs with connecting cadenzas—no variations, no special development! I used them first as encores, but my audiences seemed to like them so well that I have played them on all my recent programs.

SOME HINTS FOR THE CONCERT PLAYER

"The very first thing in playing in public is to free oneself of all distrust in one's own powers. To do this, nothing must be left to chance. One should not have to give a thought to strings, bow, etc. All should be in proper condition. Above all the violinist should play with an accompanist who is used to accompanying him. It seems superfluous to emphasize that one's program numbers must have been mastered in every detail. Only then can one defy nervousness, turning excess of emotion into inspiration.

"Acoustics play a greater part in the success of a public concert than most people realize. In some halls they are very good, as in the case of the Cleveland Hippodrome, an enormous place which holds forty-three hundred people. Here the acoustics are perfect, and the artist has those wonderful silences through which his slightest tones carry clearly and sweetly. I have played not only solos, but chamber music in this hall, and was always sorry to stop playing. In most halls the acoustic conditions are best in the evening.

"Then there is the matter of the violin. I first used a Joseph Guarnerius, a deeper toned instrument than the Jean Baptista Guadagnini I have now played for a number of years. The Guarnerius has a tone that seems to come more from within the instrument; but all in all I have found my Guadagnini, with its glassy clearness, its brilliant and limpid tone-quality, better adapted to American concert halls. If I had a Strad in the same condition as my Guadagnini the instrument would be priceless. I regretted giving up my Guarnerius, but I could not play the two violins interchangeably; for they were absolutely different in size and tone-production, shape, etc. Then my hand is so small that I ought to use the instrument best adapted to it, and to use the same instrument always. Why do I use no chin-rest? I use no chin-rest on my Guadagnini simply because I cannot find one to fit my chin. One should use a chin-rest to prevent perspiration from marring the varnish. My Rocca violin is an interesting instance of wood worn in ridges by the stubble on a man's chin.

"Strings? Well, I use a wire E string. I began to use it twelve years ago one humid, foggy summer in Connecticut. I had had such trouble with strings snapping that I cried: 'Give me anything but a gut string.' The climate practically makes metal strings a necessity, though some kind person once said that I bought wire strings because they were cheap! If wire strings had been thought of when Theodore Thomas began his career, he might never have been a conductor, for he told me he gave up the violin because of the E string. And most people will admit that hearing a wire E you cannot tell it from a gut E. Of course, it is unpleasant on the open strings, but then the open strings never do sound well. And in the highest registers the tone does not spin out long enough because of the tremendous tension: one has to use more bow. And it cuts the hairs: there is a little surface nap on the bow-hairs which a wire string wears right out. I had to have my four bows rehaired three times last season—an average of every three months. But all said and done it has been a God-send to the violinist who plays in public. On the wire A one cannot get the harmonics; and the aluminum D is objectionable in some violins, though in others not at all.

"The main thing—no matter what strings are used—is for the artist to get his audience into the concert hall, and give it a program which is properly balanced. Theodore Thomas first advised me to include in my programs short, simple things that my listeners could 'get hold of'—nothing inartistic, but something selected from their standpoint, not from mine, and played as artistically as possible. Yet there must also be something that is beyond them, collectively. Something that they may need to hear a number of times to appreciate. This enables the artist to maintain his dignity and has a certain psychological effect in that his audience holds him in greater respect. At big conservatories where music study is the most important thing, and in large cities, where the general level of music culture is high, a big solid program may be given, where it would be inappropriate in other places.

"Yet I remember having many recalls at El Paso, Texas, once, after playing the first movement of the Sibelius concerto. It is one of those compositions which if played too literally leaves an audience quite cold; it must be rendered temperamentally, the big climaxing effects built up, its Northern spirit brought out, though I admit that even then it is not altogether easy to grasp.

VIOLIN MASTERY

"Violin mastery or mastery of any instrument, for that matter, is the technical power to say exactly what you want to say in exactly the way you want to say it. It is technical equipment that stands at the service of your musical will—a faithful and competent servant that comes at your musical bidding. If your spirit soars 'to parts unknown,' your well trained servant 'technic' is ever at your elbow to prevent irksome details from hampering your progress. Mastery of your instrument makes mastery of your Art a joy instead of a burden. Technic should always be the hand-maid of the spirit.

"And I believe that one result of the war will be to bring us a greater self-knowledge, to the violinist as well as to every other artist, a broader appreciation of what he can do to increase and elevate appreciation for music in general and his Art in particular. And with these I am sure a new impetus will be given to the development of a musical culture truly American in thought and expression."