CONTENTS

XXI

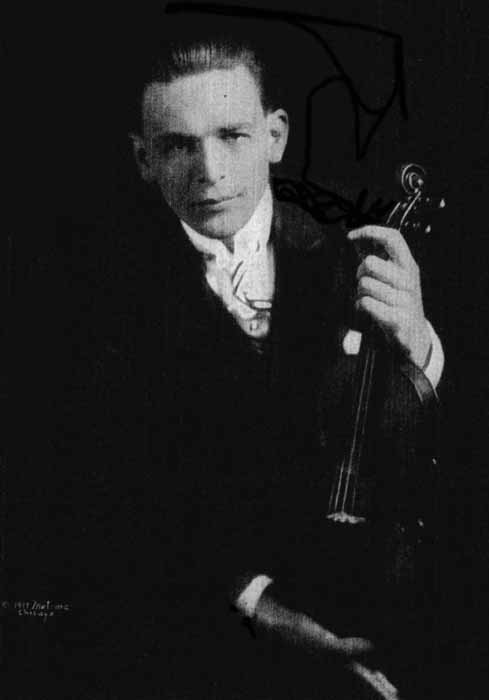

ALBERT SPALDING

THE MOST IMPORTANT FACTOR IN THE

DEVELOPMENT OF AN ARTIST

For the duration of the war Albert Spalding

the violinist became Albert Spalding

the soldier. As First Lieutenant in the Aviation

Service, U.S.A., he maintained the

ideals of civilization on the Italian front

with the same devotion he gave to those of Art

in the piping times of peace. As he himself

said not so very long ago: "You cannot do two

things, and do them properly, at the same time.

At the present moment there is more music

for me in the factories gloriously grinding out

planes and motors than in a symphony of Beethoven.

And to-day I would rather run on

an office-boy's errand for my country and do

it as well as I can, if it's to serve my country,

than to play successfully a Bach Chaconne;

and I would rather hear a well directed battery

of American guns blasting the Road of

Peace and Victorious Liberty than the combined

applause of ten thousand audiences. For

it is my conviction that Art has as much at

stake in this War as Democracy."

| Copyright by Matzene, Chicago |

Yet Lieutenant Spalding, despite the arduous demands of his patriotic duties, found time to answer some questions of the writer in the interests of "Violin Mastery" which, representing the views and opinions of so eminent and distinctively American a violinist, cannot fail to interest every lover of the Art. Writing from Rome (Sept. 9, 1918), Lieutenant Spalding modestly said that his answers to the questions asked "will have to be simple and short, because my time is very limited, and then, too, having been out of music for more than a year, I feel it difficult to deal in more than a general way with some of the questions asked."

VIOLIN MASTERY

"As to 'Violin Mastery'? To me it means effortless mastery of details; the correlating of them into a perfect whole; the subjecting of them to the expression of an architecture which is music. 'Violin Mastery' means technical mastery in every sense of the word. It means a facility which will enable the interpreter to forget difficulties, and to express at once in a language that will seem clear, simple and eloquent, that which in the hands of others appears difficult, obtuse and dull.

THE MOST IMPORTANT FACTOR IN THE DEVELOPMENT

OF AN ARTIST

"As to the processes, mental and technical, which make an artist? These different processes, mental and technical, are too many, too varied and involved to invite an answer in a short space of time. Suffice it to say that the most important mental process, to my mind, is the development of a perception of beauty. All the perseverance in the study of music, all the application devoted to it, is not worth a tinker's dam, unless accompanied by this awakening to the perception of beauty. And with regard to the influence of teachers? Since all teachers vary greatly, the student should not limit himself to his own personal masters. The true student of Art should be able to derive benefit and instruction from every beautiful work of Art that he hears or sees; otherwise he will be limited by the technical and mental limitations of his own prejudices and jealousies. One's greatest difficulties may turn out to be one's greatest aids in striving toward artistic results. By this I mean that nothing is more fatally pernicious for the true artist than the precocious facility which invites cheap success. Therefore I make the statement that one's greatest difficulties are one's greatest facilities.

A LESS DEVELOPED PHASE OF VIOLIN TECHNIC

"In the technical field, the phase of violin technic which is less developed, it seems to me is, in most cases, bowing. One often notes a highly developed left hand technic coupled with a monotonous and oftentimes faulty bowing. The color and variety of a violinist's art must come largely from his intimate acquaintance with all that can be accomplished by the bow arm. The break or change from a down-bow to an up-bow, or vice versa, should be under such control as to make it perceptible only when it may be desirable to use it for color or accentuation.

GOOD AND BAD HANDS: MENTAL STUDY

"The influence of the physical conformation of bow hand and string hand on actual playing? There are no 'good' or 'bad' bow hands or string hands (unless they be deformed); there are only 'good' and 'bad' heads. By this I mean that the finest development of technic comes from the head, not from the hand. Quickness of thought and action is what distinguishes the easy player from the clumsy player. Students should develop mental study even of technical details—this, of course, in addition to the physical practice; for this mental study is of the highest importance in developing the student so that he can gain that effortless mastery of detail of which I have already spoken.

ADVANTAGE AND DISADVANTAGE OF CONCERT ATTENDANCE

FOR THE STUDENT

"Concerts undoubtedly have great value in developing the student technically and mentally; but too often they have a directly contrary effect. I think there is a very doubtful benefit to be derived from the present habit, as illustrated in New York, London, or other centers, of the student attending concerts, sometimes as many as two or three a day. This habit dwarfs the development of real appreciation, as the student, under these conditions, can little appreciate true works of art when he has crammed his head so full of truck, and worn out his faculties of concentration until listening to music becomes a mechanical mental process. The indiscriminate attending of concerts, to my mind, has an absolutely pernicious effect on the student.

NATIONALITY AS A FORMATIVE INFLUENCE

"Nationality and national feeling have a very real influence in the development of an artist; but this influence is felt subconsciously more than consciously, and it reacts more on the creative than on the interpretative artist. By this I mean that the interpretative artist, while reserving the right to his individual expression, should subject himself to what he considers to have been the artistic impulse, the artistic intentions of the composer. As to type music to whose appeal I as an American am susceptible, I confess to a very sympathetic reaction to the syncopated rhythms known as 'rag-time,' and which appear to be especially American in character." For the benefit of those readers who may not chance to know it, Lieutenant Spalding's "Alabama," a Southern melody and dance in plantation style, for violin and piano, represents a very delightful creative exploitation of these rhythms. The writer makes mention of the fact since with regard to this and other of his own compositions Lieutenant Spalding would only state: "I felt that I had something to say and, therefore, tried to say it. Whether what I have to say is of any interest to others is not for me to judge.

PLAYING WHILE IN SERVICE

"Do I play at all while in Service? I gave up all playing in public when entering the Army a year ago, and to a great extent all private playing as well. I have on one or two occasions played at charity concerts during the past year, once in Rome, and once in the little town in Italy near the aviation camp at which I was stationed at the time. I have purposely refused all other requests to play because one cannot do two things at once, and do them properly. My time now belongs to my country: When we have peace again I shall hope once more to devote it to Art."