CONTENTS

XII

HANS LETZ

THE TECHNIC OF BOWING

Hans Letz, the gifted Alsatian violinist, is

well fitted to talk on any phase of his Art. A

pupil of Joachim (he came to this country in

1908), he was for three years concertmaster

of the Thomas orchestra, appearing as a solo

artist in most of our large cities, and was not

only one of the Kneisels (he joined that organization

in 1912), but the leader of a quartet

of his own. As a teacher, too, he is active in

giving others an opportunity to apply the lessons

of his own experience.

VIOLIN MASTERY

When asked for his definition of the term, Mr. Letz said: "There can be no such thing as an absolute mastery of the violin. Mastery is a relative term. The artist is first of all more or less dependent on circumstances which he cannot control—his mood, the weather, strings, a thousand and one incidentals. And then, the nearer he gets to his ideal, the more apt his ideal is to escape him. Yet, discounting all objections, I should say that a master should be able to express perfectly the composer's idea, reflected by his own sensitive soul.

THE KEY TO INTERPRETATION

"The bow is the key to this mastery in expression, in interpretation: in a lesser degree the left hand. The average pupil does not realize this but believes that mere finger facility is the whole gist of technic. Yet the richest color, the most delicate nuance, is mainly a matter of bowing. In the left hand, of course, the vibrato gives a certain amount of color effect, the intense, dramatic tone quality of the rapid vibrato is comparable on the violin to the tremulando of the singer. At the same time the vibrato used to excess is quite as bad as an excessive tremulando in the voice. But control of the bow is the key to the gates of the great field of declamation, it is the means of articulation and accent, it gives character, comprising the entire scale of the emotions. In fact, declamation with the violin bow is very much like declamation in dramatic art. And the attack of the bow on the string should be as incisive as the utterance of the first accented syllable of a spoken word. The bow is emphatically the means of expression, but only the advanced pupil can develop its finer, more delicate expressional possibilities.

THE TECHNIC OF BOWING

"Genius does many things by instinct. And it sometimes happens that very great performers, trying to explain some technical function, do not know how to make their meaning clear. With regard to bowing, I remember that Joachim (a master colorist with the bow) used to tell his students to play largely with the wrist. What he really meant was with an elbow-joint movement, that is, moving the bow, which should always be connected with a movement of the forearm by means of the elbow-joint. The ideal bow stroke results from keeping the joints of the right arm loose, and at the same time firm enough to control each motion made. A difficult thing for the student is to learn to draw the bow across the strings at a right angle, the only way to produce a good tone. I find it helps my pupils to tell them not to think of the position of the bow-arm while drawing the bow across the strings, but merely to follow with the tips of the fingers of the right hand an imaginary line running at a right angle across the strings. The whole bow then moves as it should, and the arm motions unconsciously adjust themselves.

RHYTHM AND COLOR

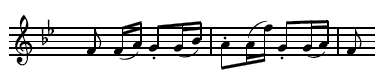

"Rhythm is the foundation of all music—not rhythm in its metronomic sense, but in the broader sense of proportion. I lay the greatest stress on the development of rhythmic sensibility in the student. Rhythm gives life to every musical phrase." Mr. Letz had a Brahms' quartet open on his music stand. Playing the following passage, he said:

"In order to give this phrase its proper rhythmic value, to express it clearly, plastically, there must be a very slight separation between the sixteenths and the eighth-note following them. This—the bow picked up a trifle from the strings—throws the sixteenths into relief. As I have already said, tone color is for the main part controlled by the bow. If I draw the bow above the fingerboard instead of keeping it near the bridge, I have a decided contrast in color. This color contrast may always be established: playing near the bridge results in a clear and sharp tone, playing near the fingerboard in a veiled and velvety one.

SUGGESTIONS IN TEACHING

"I find that, aside from the personal illustration absolutely necessary when teaching, that an appeal to the pupil's imagination usually bears fruit. In developing tone-quality, let us say, I tell the pupil his phrases should have a golden, mellow color, the tonal equivalent of the hues of the sunrise. I vary my pictures according to the circumstances and the pupil, in most cases, reacts to them. In fast bowings, for instance, I make three color distinctions or rather sound distinctions. There is the 'color of rain,' when a fast bow is pushed gently over the strings, while not allowed to jump; the 'color of snowflakes' produced when the hairs of the bow always touch the strings, and the wood dances; and 'the color of hail' (which seldom occurs in the classics), when in the real characteristic spiccato the whole bow leaves the string."

THE ART AND THE SCHOOLS

In reply to another question, Mr. Letz added: "Great violin playing is great violin playing, irrespective of school or nationality. Of course the Belgians and French have notable elegance, polish, finish in detail. The French lay stress on sensuous beauty of tone. The German temperament is perhaps broader, neglecting sensuous beauty for beauty of idea, developing the scholarly side. Sarasate, the Spaniard, is a unique national figure. The Slavs seem to have a natural gift for the violin—perhaps because of centuries of repression—and are passionately temperamental. In their playing we find that melancholy, combined with an intense craving for joy, which runs through all Slavonic music and literature. Yet, all said and done, Art is and remains first of all international, and the great violinist is a great artist, no matter what his native land."