CONTENTS

XIX

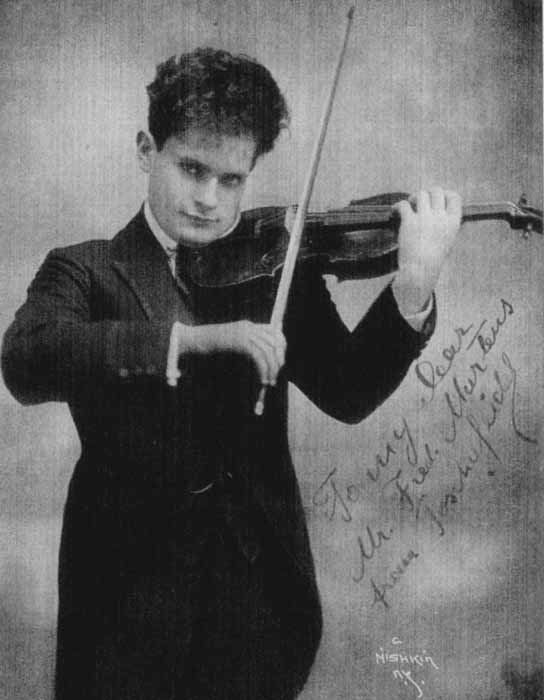

TOSCHA SEIDEL

HOW TO STUDY

Toscha Seidel, though one of the more

recent of the young Russian violinists who represent

the fruition of Professor Auer's formative

gifts, has, to quote H.F. Peyser, "the

transcendental technic observed in the greatest

pupils of his master, a command of mechanism

which makes the rough places so plain that the

traces of their roughness are hidden to the unpracticed

eye." He commenced to study the

violin seriously at the age of seven in Odessa,

his natal town, with Max Fiedemann, an Auer

pupil. A year and a half later Alexander

Fiedemann heard him play a De Bériot concerto

in public, and induced him to study at

the Stern Conservatory in Berlin, with Brodsky,

a pupil of Joachim, with whom he remained

for two years.

It was in Berlin that the young violinist reached the turning point of his career. "I was a boy of twelve," he said, "when I heard Jascha Heifetz play for the first time. He played the Tschaikovsky concerto, and he played it wonderfully. His bowing, his fingering, his whole style and manner of playing so greatly impressed me that I felt I must have his teacher, that I would never be content unless I studied with Professor Auer! In 1912 I at length had an opportunity to play for the Professor in his home at Loschivitz, in Dresden, and to my great joy he at once accepted me as a pupil.

STUDYING WITH PROFESSOR AUER

"Studying with Professor Auer was a revelation. I had private lessons from him, and at the same time attended the classes at the Petrograd Conservatory. I should say that his great specialty, if one can use the word specialty in the case of so universal a master of teaching as the Professor, was bowing. In all violin playing the left hand, the finger hand, might be compared to a perfectly adjusted technical machine, one that needs to be kept well oiled to function properly. The right hand, the bow hand, is the direct opposite—it is the painter hand, the artist hand, its phrasing outlines the pictures of music; its nuances fill them with beauty of color. And while the Professor insisted as a matter of course on the absolute development of finger mechanics, he was an inspiration as regards the right manipulation of the bow, and its use as a medium of interpretation. And he made his pupils think. Often, when I played a passage in a concerto or sonata and it lacked clearness, he would ask me: 'Why is this passage not clear?' Sometimes I knew and sometimes I did not. But not until he was satisfied that I could not myself answer the question, would he show me how to answer it. He could make every least detail clear, illustrating it on his own violin; but if the pupil could 'work out his own salvation' he always encouraged him to do so.

Toscha Seidel

"Most teachers make bowing a very complicated affair, adding to its difficulties. But Professor Auer develops a natural bowing, with an absolutely free wrist, in all his pupils; for he teaches each student along the line of his individual aptitudes. Hence the length of the fingers and the size of the hand make no difference, because in the case of each pupil they are treated as separate problems, capable of an individual solution. I have known of pupils who came to him with an absolutely stiff wrist; and yet he taught them to overcome it.

ARTIST PUPILS AND AMATEUR STUDENTS

"As regards difficulties, technical and other, a distinction might be made between the artist and the average amateur. The latter does not make the violin his life work: it is an incidental. While he may reasonably content himself with playing well, the artist-pupil must achieve perfection. It is the difference between an accomplishment and an art. The amateur plays more or less for the sake of playing—the 'how' is secondary; but for the artist the 'how' comes first, and for him the shortest piece, a single scale, has difficulties of which the amateur is quite ignorant. And everything is difficult in its perfected sense. What I, as a student, found to be most difficult were double harmonics—I still consider them to be the most difficult thing in the whole range of violin technic. First of all, they call for a large hand, because of the wide stretches. But harmonics were one of the things I had to master before Professor Auer would allow me to appear in public. Some find tenths and octaves their stumbling block, but I cannot say that they ever gave me much trouble. After all, the main thing with any difficulty is to surmount it, and just how is really a secondary matter. I know Professor Auer used to say: 'Play with your feet if you must, but make the violin sound!' With tenths, octaves, sixths, with any technical frills, the main thing is to bring them out clearly and convincingly. And, rightly or wrongly, one must remember that when something does not sound out convincingly on the violin, it is not the fault of the weather, or the strings or rosin or anything else—it is always the artist's own fault!

HOW TO STUDY

"Scale study—all Auer pupils had to practice scales every day, scales in all the intervals—is a most important thing. And following his idea of stimulating the pupil's self-development, the Professor encouraged us to find what we needed ourselves. I remember that once—we were standing in a corridor of the Conservatory—when I asked him, 'What should I practice in the way of studies?' he answered: 'Take the difficult passages from the great concertos. You cannot improve on them, for they are as good, if not better, as any studies written.' As regards technical work we were also encouraged to think out our own exercises. And this I still do. When I feel that my thirds and sixths need attention I practice scales and original figurations in these intervals. But genuine, resultful practice is something that should never be counted by 'hours.' Sometimes I do not touch my violin all day long; and one hour with head work is worth any number of days without it. At the most I never practice more than three hours a day. And when my thoughts are fixed on other things it would be time lost to try to practice seriously. Without technical control a violinist could not be a great artist; for he could not express himself. Yet a great artist can give even a technical study, say a Rode étude, a quality all its own in playing it. That technic, however, is a means, not an end, Professor Auer never allowed his pupils to forget. He is a wonderful master of interpretation. I studied the great concertos with him—Beethoven, Bruch, Mendelssohn, Tschaikovsky, Dvořák, the Brahms concerto (which I prefer to any other); the Vieuxtemps Fifth and Lalo (both of which I have heard Ysaye, that supreme artist who possesses all that an artist should have, play in Berlin); the Elgar concerto (a fine work which I once heard Kreisler, an artist as great as he is modest, play wonderfully in Petrograd), as well as other concertos of the standard repertory. And Professor Auer always sought to have us play as individuals; and while he never allowed us to overstep the boundaries of the musically esthetic, he gave our individuality free play within its limits. He never insisted on a pupil accepting his own nuances of interpretation because they were his. I know that when playing for him, if I came to a passage which demanded an especially beautiful legato rendering, he would say: 'Now show how you can sing!' The exquisite legato he taught was all a matter of perfect bowing, and as he often said: 'There must be no such thing as strings or hair in the pupil's consciousness. One must not play violin, one must sing violin!'

FIDDLE AND STRINGS

"I do not see how any artist can use an instrument which is quite new to him in concert. I never play any but my own Guadagnini, which is a fine fiddle, with a big, sonorous tone. As to wire strings, I hate them! In the first place, a wire E sounds distinctly different to the artist than does a gut E. And it is a difference which any violinist will notice. Then, too, the wire E is so thin that the fingers have nothing to take hold of, to touch firmly. And to me the metallic vibrations, especially on the open strings, are most disagreeable. Of course, from a purely practical standpoint there is much to be said for the wire E.

VIOLIN MASTERY

"What is violin mastery as I understand it? First of all it means talent, secondly technic, and in the third place, tone. And then one must be musical in an all-embracing sense to attain it. One must have musical breadth and understanding in general, and not only in a narrowly violinistic sense. And, finally, the good God must give the artist who aspires to be a master good hands, and direct him to a good teacher!"